Colleges are working hard to bring in additional students. And there is such a cost to bringing in each student, that you don’t want to lose them through an enrollment and registration process that is confusing or simply takes too long.

Or as Kevin Pollock, the president of St. Clair County Community College, remarks pointedly, “Any time your students have to walk across campus unnecessarily from one office to another in trying to resolve an issue is an opportunity for them to walk to their car and leave.”

Where are the Bottlenecks

Kevin Pollock suggests that a key task of your student success task force or retention committee is walking through each step of the student’s experience on your campus, from admission on, to take an in-depth look at where students run into bottlenecks, delays in service, or where there might be missed opportunities to better support their academic success. Pollock recommends trying an array of data collection methods from surveys to focus groups to “mystery shopper” exercises (in which a member of the task force walks through a process in person to get a first-hand perspective of its efficiency).

“How does a student register for classes?” Pollock asks. “Is the process productive or not, and if not, how can you fix it? When is financial aid released, and how do students get their information? What about your bookstore — are all the items there on time, and have students received their financial aid in time to buy them before classes start?” Often, Pollock suggests, walking through the processes and procedures of the student experience will reveal where a policy or a process proves a hindrance, rather than a help, to students.

One exercise that we recommend is to bring your department heads and key managers together and lay a rope out over the floor, using it to simulate the path a student takes from admission to sitting in the classroom. Points along the rope can represent particular steps (whether physical interactions or virtual ones), from visiting the admissions office to meeting with a counselor. Often, when you carry out this exercise with professionals on a campus, you may find that there is disagreement among the officials in the room on the sequence of steps. Surfacing these disagreements together can help you identify where in the process students may be left confused or misdirected.

Another tactic: Interview a student who recently navigated the process. Where did they find delays?

Finding the Time to Improve Service

Rick Weems, past assistant vice president for enrollment at Southern Oregon University, who transitioned his institution’s enrollment service to a one-stop model, remarks that often managers hesitate to pursue improvements in service because they don’t believe they have the time. Yet actually, Weems notes, improved services equal significant savings in staff time in the long-term because improved service decreases lines and call volume.

The key is to ask not “How can I provide service in a way that is friendlier to the student?” but “How can I offer service in such a way that I minimize the demand on the student’s time and make visits to my office fewer?”

Here’s an example. Suppose your registrar sees very long lines during peak times such as the first few days of each term. One manager might respond in a service-oriented way by asking for volunteers to walk up and down those lines throughout the day, handing out forms and helping students to fill them out by the time the students reach the front of the line. This, however, is not the best solution available; it takes either staff time or time to train volunteers, and you still won’t have decreased that line or the frustration your students and staff will feel. And as your staff are busy tending the lines, incoming calls and emails will also get backed up.

Here is Weems’ solution. Have one or two managers devote their time during those peak days to answering email inquiries quickly. Suppose your managers respond to student emails within the hour, while your front-line staff handle the line of students. As students get their questions answered quickly, fewer of them will need to come to that line. “A year later,” Weems remarks, “you have a shorter line that doesn’t go out the door.”

Or put as many answers as possible on the web, and direct students to them. “Often, students just need to check status,” Weems comments. “If you give them a way to do that through a secure connection, you get a smaller line.”

“It all boils down to turnaround time. The faster you turnaround the service, the less traffic you’ll have.”

Rick Weems

Here’s another example. If you know that your front-line staff will need to interrupt your experts on particular issues frequently during peak times, put those experts on an “interrupt” schedule. Rotate through on-call admissions or financial aid staff members. When they are designated “on call,” they have a block on their schedule and are available to be interrupted by front-line staff with questions during that shift. In this way, interruptions are planned, and your key staff can plan productivity and time management around those shifts.

A Useful Tool

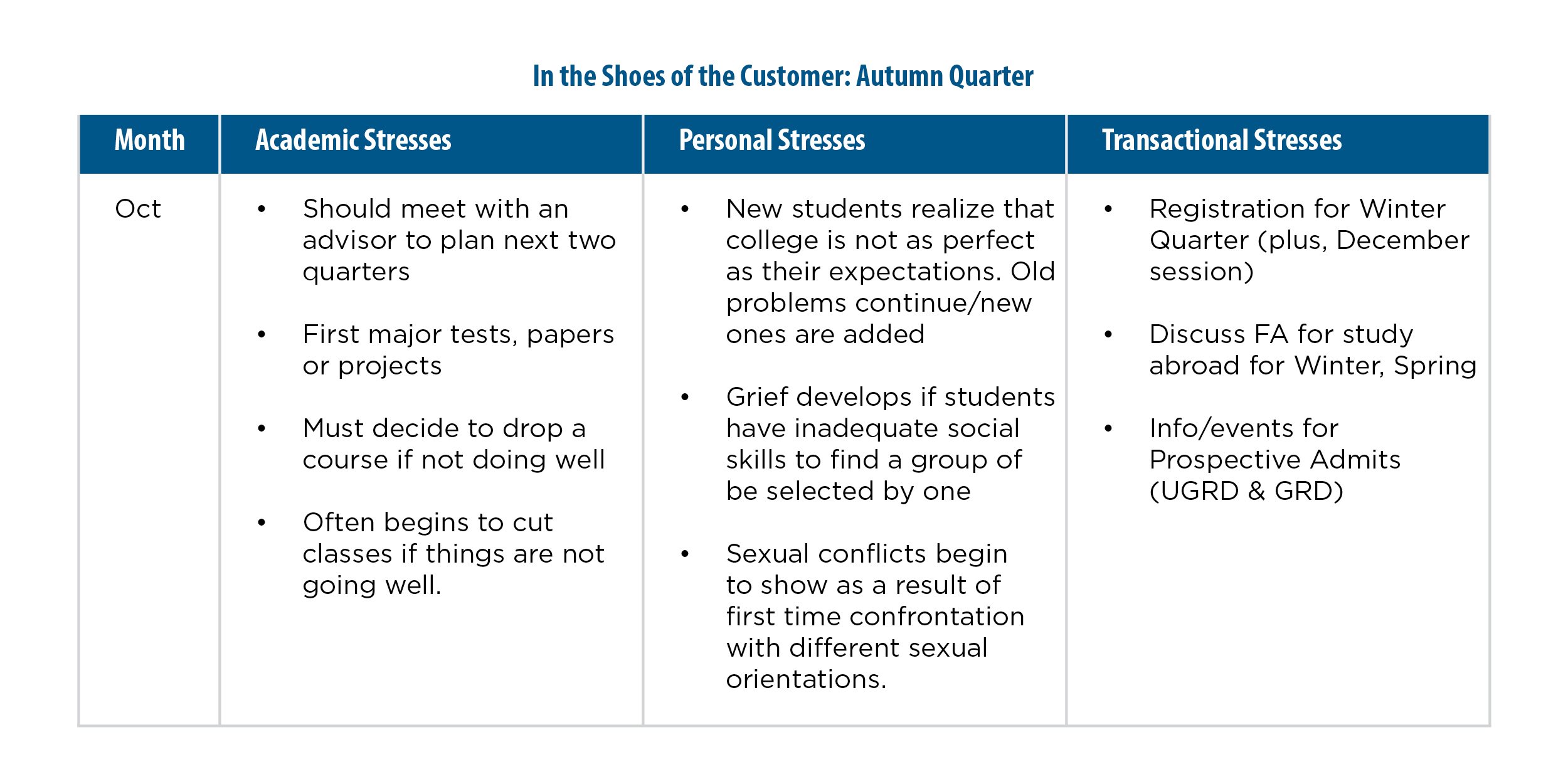

One resource that Susan Leigh provided her enrollment staff at DePaul University is a three-column chart that tracks, over the course of an academic year, common worries or stress points for students:

- Column A tracks key points on the academic calendar, such as registration, midterm exams, and final exams.

- Column B tracks transactional points, such as the FAFSA due date, the deadline for the housing contract, etc.

- Column C tracks common student life stress points, based on student development research, such as a wave of homesickness six weeks into the first term.

This tool helps guide front-line staff as they respond to student inquiries by encouraging greater awareness of an inquiry’s context.

SAMPLE

Solving the Structural Issues: the One-Stop Approach

Housing enrollment services teams within one reporting structure and one physical location on campus can be a key strategy to start the conversations and the collaborative work needed to improve service to students.

A one-stop center creates a single point of contact, allowing students to approach one front desk and get their questions answered, whether those questions are best directed to financial aid, student records, admissions, cashiering, one card services, or other critical functions.

Weems notes that a one-stop approach may not be necessary for all institutions, but that it would be beneficial for many.

“This depends on the culture of the institution,” Weems notes, “and how prepared the staff are to work across lines. You can accomplish a lot without a physical, one-stop structure if the staff are willing to work across silos and can eliminate student runaround without it. But at many institutions, staff are neither accustomed nor ready to achieve this.”

Training Your Enrollment Services Staff in Customer Service

Weems notes that while transitioning to a one-stop model for enrollment services can serve to break down “physical” silos successfully, simply merging offices or placing them all under one vice president is not, in and of itself, enough to improve service to the student.

“You won’t get the desired result unless you deal with the emotional and mental silos. You have to get everyone on the same page—that this is now one unit, not three units. That’s hard; it takes everyone’s commitment.”

Rick Weems

“To make service work in the modern educational enterprise,” Weems adds, “you have to become committed to cross-training.”

Weems offers this example to illustrate the point: “Up to 50% of incoming student inquiries are likely to be questions related to financial aid. If those all have to be answered by front-line financial aid staff, then response time is going to crawl toward a standstill. The more that front-line staff across enrollment services can understand and answer basic financial aid questions, the better equipped you will be to handle volume.”

Also, consider developing a core list of commonly asked questions across enrollment services. There might be 30, or 50, or 70 such questions. “Each person who answers the phones or sees students at the front counters needs to know the answers to these questions,” Weems advises. “This will ensure that students can receive answers to these common questions without the need to take up a specialist’s time unnecessarily.” Also, ensure that these FAQs are available (and easy to find) online.