also by Robert E. Johnson, Ph.D.

(Learn more in the recorded webcast: The Future of Work and the Academy)

Higher education and the coveted bachelor’s degree was once the essential launch pad to economic stability. Now, it seems it is something more. In to a new report published by Brookings, “Mortality and morbidity in the 21st century,” Princeton professors Anne Case and Angus Deaton explore the patterns and trends that have led to a decline in the life expectancy of middle-aged white people without college degrees since the late 1990s.

Spoiler alert: education is the key distinction, and differences in life expectancy do not appear due simply to an economic division.

In this paper, we will take a look at the changing landscape of work and what this means for higher education. We’ll look particularly at manufacturing. Note: All segments of our economy are in some form of disruption. Manufacturing is an obvious and easy industry to use as an example as the devastation can be seen and understood. Rising automation and machine intelligence will creep into and replace the knowledge workers with the same voracity with which the physical workers have been supplanted:

How We Got Here

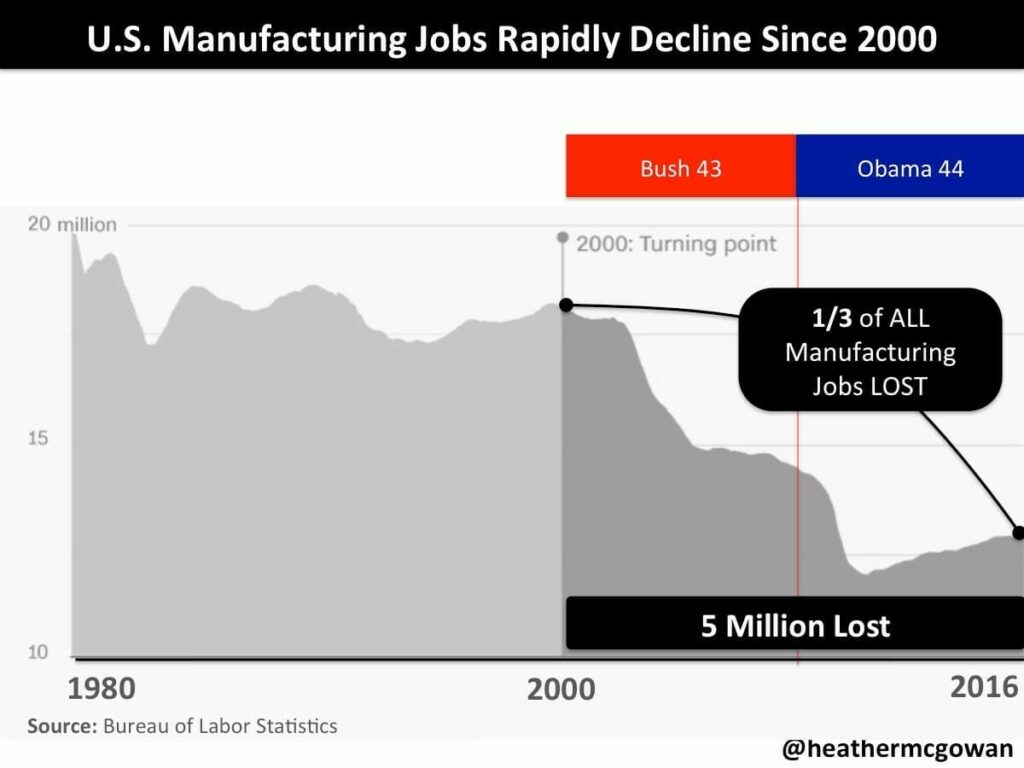

We lost a third of all manufacturing jobs between 2001 and 2016. The Great Recession in 2008 accelerated this job loss. This is what started in the late 1990s — first and foremost, the shift from a manufacturing economy to a service economy.

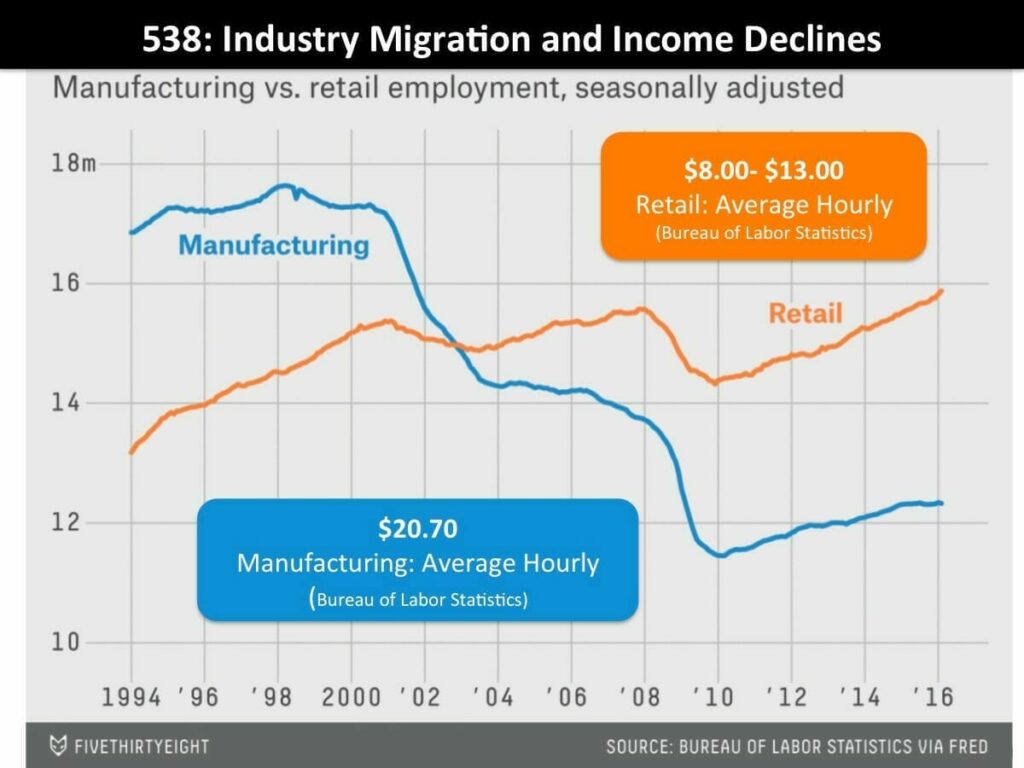

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, as reported by Nate Silver, the average factory worker earns more than $25 an hour before overtime; the typical retail worker makes less than $18 an hour—in many cases, a lot less. But this goes beyond income—it hits at identity. Being a manufacturing worker is a blue-collar job that often came with membership in a union. These two things together created a sense of pride, offered some guaranteed protections, and, perhaps most importantly, provided an identity. Manufacturing jobs and the related identity were passed down from one generation to the next–until, in the late 90s, they started to disappear all together.

Many will blame trade deals—and we will not get into that—but much of the research we found, notably the Ball State study, suggests these jobs were lost to technology. When the manufacturing jobs disappeared, the blue collars were traded in for “pink collars,” a term coined to distinguish service jobs that are often predominantly held by women. Pink-collar jobs pay less and, according to research aggregated by the New York Times, carry a stigma for some men, contributing to the loss of identity and consequent desperation.

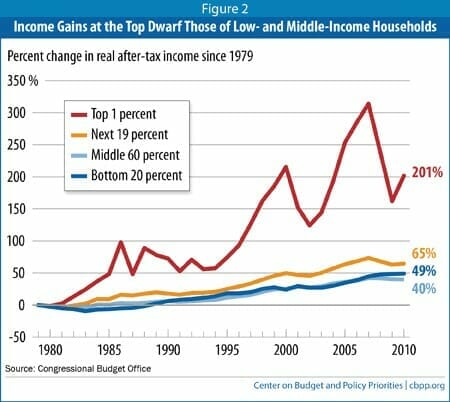

What also occurred during this period was the rise of technology and the rise of the information economy. This shift has greater long term implications, many not yet realized. The impact of both of these trends resulted in an erosion of the middle class. In the last 45 years, according to The Pew Research Center, we have lost 11% of the middle class, with 4% landed in the lowest income level and 7% going to the upper middle and highest income brackets. This disappearing middle class and loss of opportunity for those with limited education has fueled a rise in populist movements around the globe with related backlashes against women, minorities, and immigrants—whom some deem responsible for the loss of opportunity.

Adapting to the Next Industrial Revolution

These nationalist, isolationist, and populist responses are an effort, in our view, to halt the inevitability of a hyper-connected global society where anything mentally routine or predictable will be achieved by the actor—whether human (of any race, gender, or nationality) or machine—most cost-effective at completing the task.

Consider some key projections:

- By 2020, 65% of jobs will require training beyond high school and 35% of jobs will require at minimum a bachelor’s degree. (Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce)

- Currently only 59% of the US has any education beyond high school and less than 33% of our populace has a bachelor’s degree. (United States Census 2015)

- According to a recent study by Georgetown’s Public Policy Institute, based upon our current pipeline of students, we will fall 5 million short in the workers we need with post secondary credentials.

Looking backward, according to the College Board, a typical individual with a bachelor’s degree could expect to earn 67% more in 2015 than an individual with only a high school diploma. This adds up to millions of dollars over the long arc of a career. Will this continue to be true as the cost of education continues to increase and as we see the rise of machines that, for many tasks, outperform those university-educated graduates? That remains to be seen.

We have considerable work to do in re-conceiving our systems of education to match our new economies in cost, access, and relevance. What is clear to us is that learning agility—the ability to learn and adapt to rise up with advancing technology capability—is a public good that creates not only economic opportunity but also social fabric and individual identity, including, perhaps, human longevity.

Enter Technology and Longevity – For Some

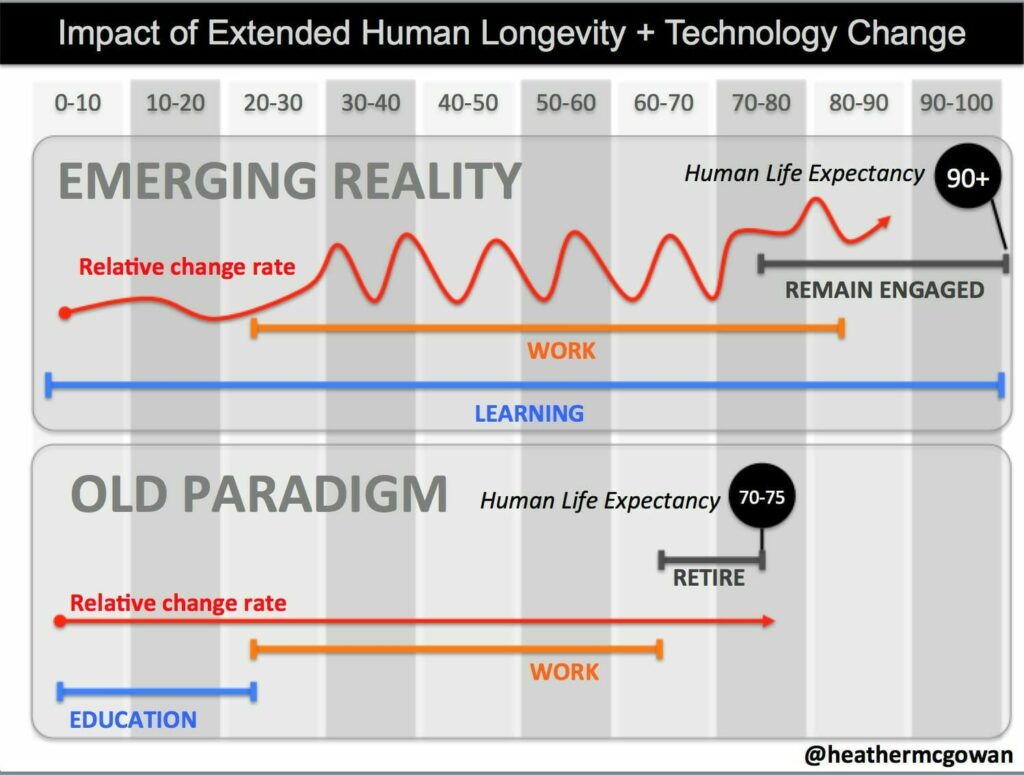

All of the above was before factoring in the impact of two amplifying and disrupting forces: technology and longevity. We have made considerable leaps in human longevity. The life expectancy of someone born in 1950 was 69 and today it is 80 and is expected to reach 100 in the next few decades. This doesn’t just mean longer life, this means longer work. We can expect the work career as a matter of both social and economic necessity to be at least a decade longer. This longer career arc is happening as the velocity of change is becoming the most acute.

The chart below depicts the emerging reality of work and life expectancy compared to the old paradigm of work and life expectancy. Note that in the old paradigm the rate of change is static, and in the emerging reality it is dynamic. This longer life expectancy for a generation that did not grow up with technology but now find themselves in a rapidly changing world—helps to explain why many dislocated workers turn to populist identity politics and feel left out of the next industrial revolution.

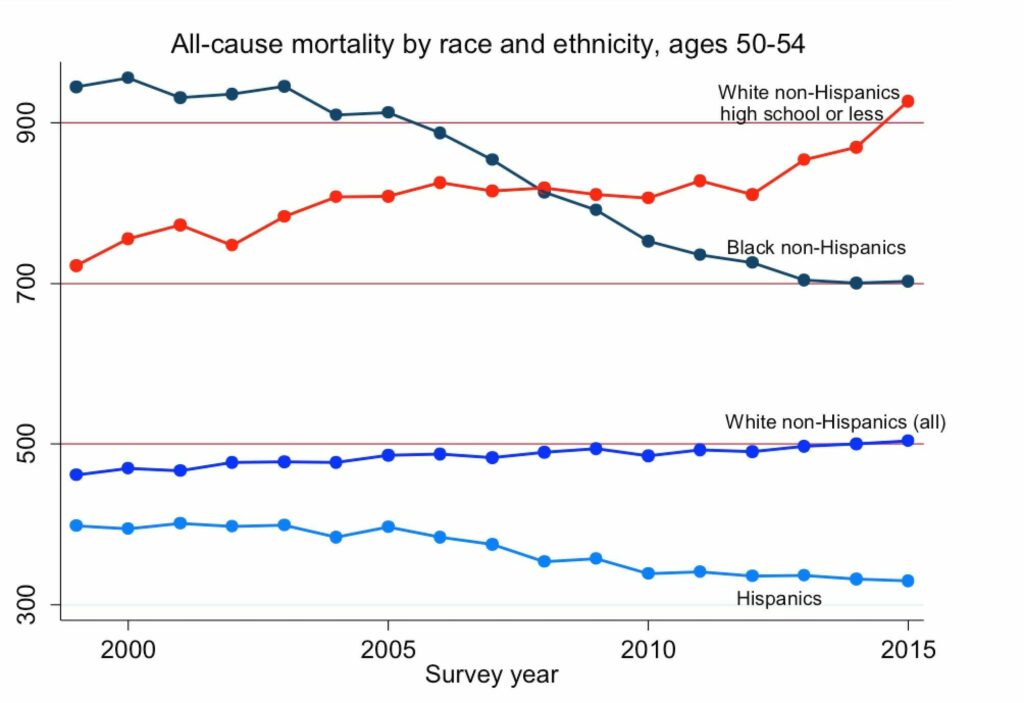

Furthermore, the section of our population that is not experiencing these gains in longevity, especially as of late, is non-Hispanic white individuals without a college degree. There has long been a correlation between education and longevity, but now as we see a rise in what has been dubbed “deaths of despair,” deaths from opioid and alcohol overdoses, suicides, homicides, and substance-related automobile accidents. This rise correlates with lower levels of educational attainment.

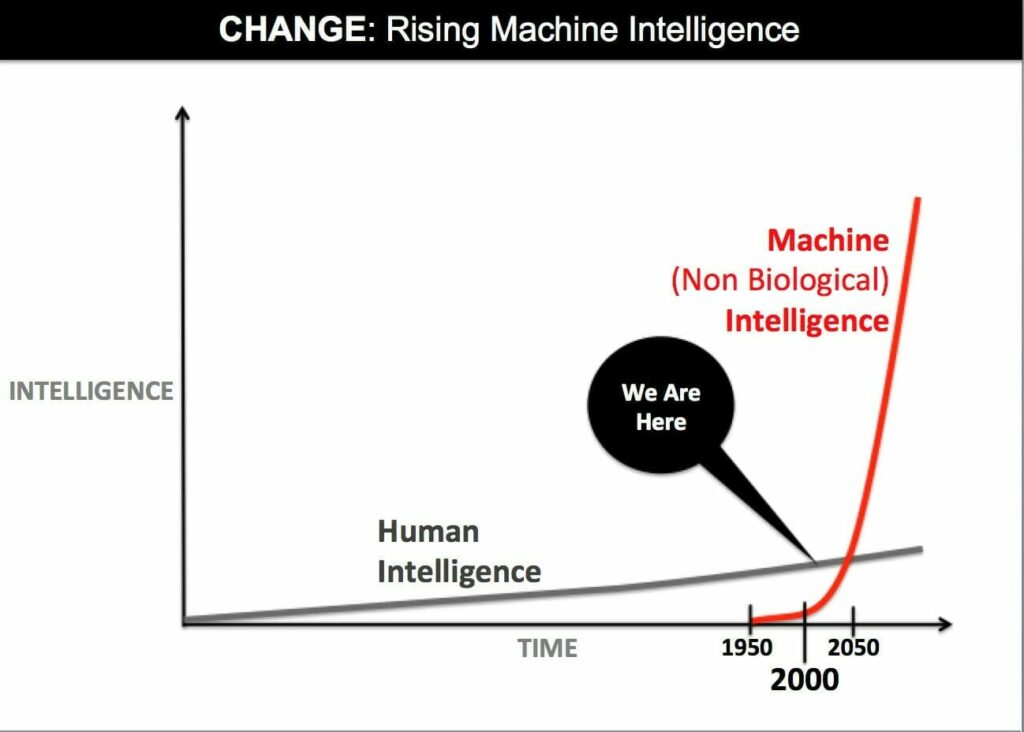

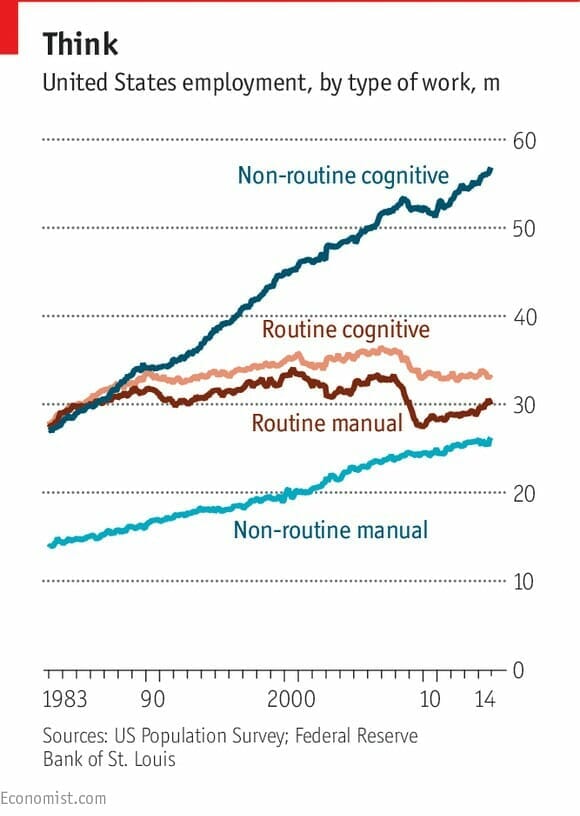

Rapid advances in technology in the past decade and, more importantly, those expected in the next decade plus, may render as much as half of our current work replaceable by automation. A physical robot and/or a software algorithm can replace anything physically or mentally routine or predictable. Automation has already decimated high-paying middle class jobs in manufacturing, as evidenced by the loss of 6 million jobs between 2000-2009, of which 88% were lost to technology.

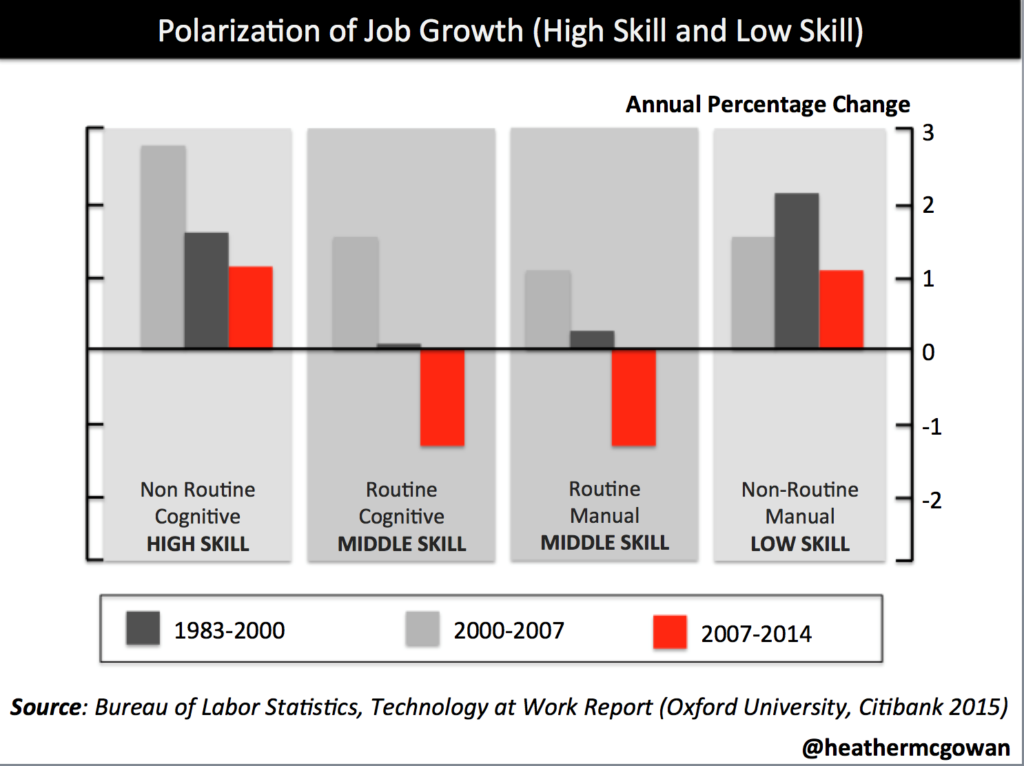

That wave of automation that already decimated manufacturing may just hit the service sector even more swiftly. Since January 2017, we have seen a loss of 61,000 jobs in retail according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The replacement by machine intelligence is not limited to low skill jobs, as rising machine intelligence could replace more than half of what we currently do under the banner of all human work across all industries—notably anything mentally or cognitively routine is ripe for replacement. In the last seven years alone, we have seen a further hollowing out of both routine mental and physical middle skills. Could some form of automation replace your current, or planned, job? The BBC created a Robot Calculator for such planning purposes. You can try that here.

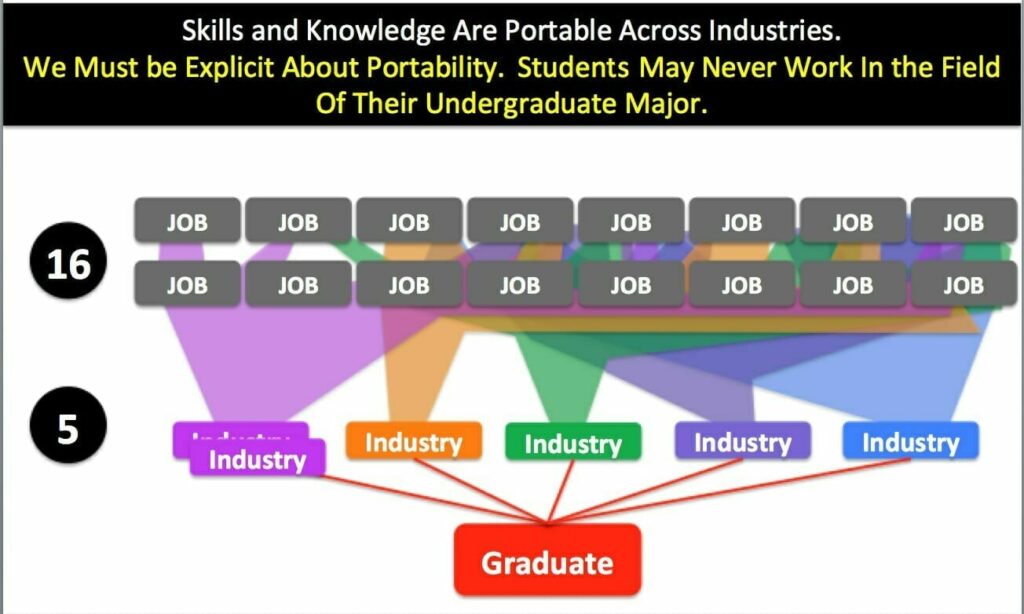

It is not simply a question of whether your skills or expertise can or cannot be replaced; we need to think differently about the professions. A landmark study by the Foundation for Young Australians projects that based upon technology changes, globalization, and longevity, young people today will have at least sixteen to seventeen distinct careers in five different industries. This study was based upon data from the McKinsey Global Institute and the World Economic Forum and is applicable to all developed countries.

With that much change ahead, how do we prepare young people for jobs that do not yet exist or to solve problems not yet known, utilizing technology that has not been created?

We cannot simply rely on our current education factory pipeline model of transferring skills and content into new professionals. We can no longer prepare people for just one job or just one industry. In fact, according in this recent article by the BBC, we need to stop thinking of the professional you want to be (end state) and focus on the skills you want to acquire (continuous). If we are preparing students for one job or only one industry—we may be committing educational malpractice.

The loss of manufacturing, and the current losses in service and retail, when combined with the threats from rising machine capabilities, place even greater pressure on the need for not just advanced study but continual study. We need to prepare students to keep pace with change and to continually develop skills that compliment rising automation and global competition. Investment firm GSV Capital estimates that in order to meet this exploding demand, education will grow from 9% to 12% of America’s GDP over the next decade.

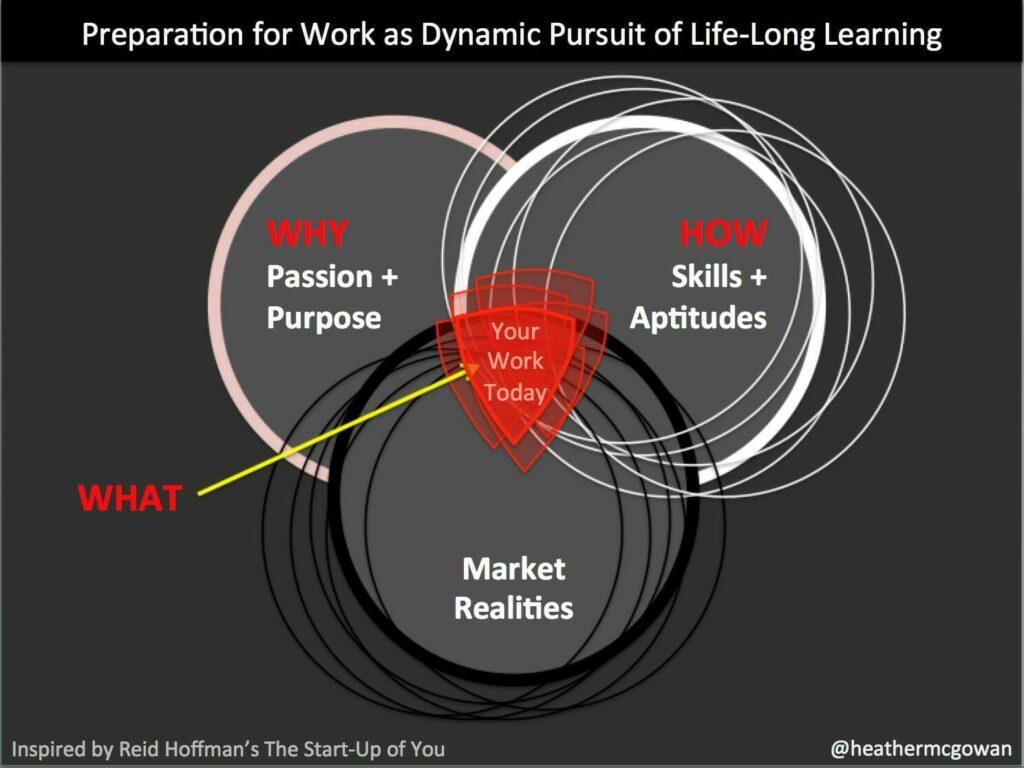

Identity Crisis: It is the Why, Not the What

Whether you are educated through high school or graduate school, we have approached education and workforce development, as John Hagel says, as a “transfer of predetermined skills and existing knowledge.” We ask young people what they want to be when they grow up before they have had much of a chance to learn their skills and aptitudes and, more importantly, discover their passion and purpose. We treat all levels of educational attainment as an end state of achievement rather than a continuous journey. As we face greater and greater velocities of change, we must shift our thinking from education with an end state to continuous, agile learning. This is the paradigm that will support the future of work to keep America competitive. Inherent in this pursuit is helping people find passion and purpose that aligns with their aptitudes and teaching them to continuously align their assets with market-valuing opportunities.

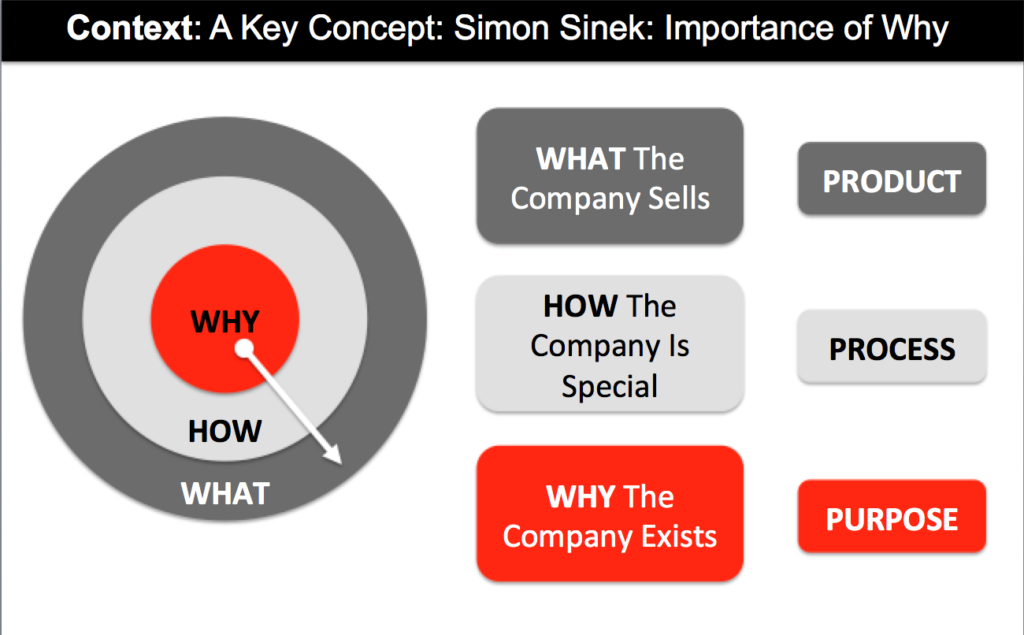

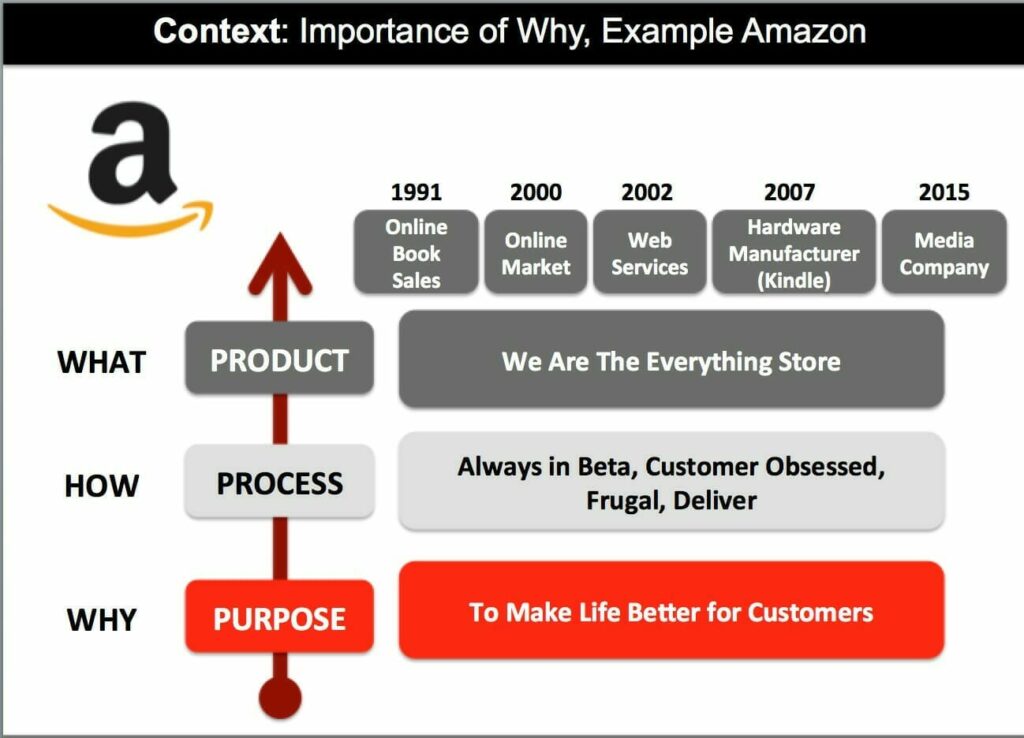

Simon Sinek’s TED Talk, “How Great Leaders Inspire Action,” and his subsequent book Start With Why both focus on how companies can communicate more than just the products and services they offer (What) and even more than how they make them (HOW), to communicate their deeper purpose and passions (WHY). His premise, expressed in the book and the talk, is that by starting with purpose you create a greater and deeper connection with your audience or customers.

The market cap of fourteen-year-old Tesla just eclipsed that of 113-year-old Ford and General Motors. This speed of change in companies must be matched by speed of adaptability in workers. The calcified mindset of self will no longer work. If higher education continues to focus on monolithic degrees in set (and siloed) educational tracks that are focused on starting salaries as a proxy for success, we may see massive failure.

When you layer in rapid rates of change where products and services (WHAT) now have fractional half-lives, establishing strong company cultures is an imperative to survive. Consider Amazon. In just twenty years, Amazon has morphed from a bookseller to an online marketplace to a web services company to a hardware manufacturer to a full-blown media company that has achieved Academy awards. The chart below depicts Amazon’s philosophical paradigm. They start with the “why,” which provides a sense of purpose: making customers’ lives better.

In higher education, we need to establish a foundation in self-discovery where students starting as young as grade school begin to explore their learning styles and cognitive preferences alongside their assessed skills and aptitudes, so that they can connect to an innate drive of passion and purpose (WHY) that they can make productive (HOW) and continually reframe in application to the emerging challenges they face (WHAT). This framework is an imperative integral to agile, life long learning and is a key mindset that must be established before chasing skillsets.

Market realities will change dramatically as machine intelligence advances, forcing a re-framing of the HOW, creating an imperative to add or increase skills and alter applications of knowledge to form a new type of work today (WHAT). Having passion with a sense of purpose (WHY) will also impact longevity.

Why Might Our Life Depend Upon It?

The correlation between education and greater longevity has been well documented—with many logical examples.

For instance, better health literacy creates better health outcomes.

The researchers, Anne Case and Angus Deaton, suggest that the trend of lower health outcomes, so far, is due not simply to loss of income but, instead, an accumulation of factors. Lower incomes reduce home ownership and delay both marriage and family or create multiple children with multiple parents—those things together, potentially, untether the social fabric that once held our communities together. With the decline of purpose and the scramble to economically make ends meet, individuals work more disconnected jobs, creating greater stress levels. With greater access to pharmaceuticals, notably opioids, to ease that stress and pain, we see a rise in addictions to add fuel to the fire.

The question now becomes how do we instill a sense of purpose to fuel life long learning and an educational ethos in a population that has long defined themselves more on the work they do than the learning that enables that work. Segments of our population that have survived and, in the last industrial revolution even thrived, with an education that ended at high school and a career path and purpose that was inherited from a prior generation. This is a massive cultural shift that is necessary to create a future that includes all our populace.

This shift, so far impacting individuals without a college degree, is one to pay attention as it is has left a large part of our populace behind. As NYT writer Anand Giridharadas describes in his 2016 TED talk A Letter To All Who Have Lost In This Era, many of us have charged forward with enthusiasm about this new world and all of the possibilities of on demand cars and the gig economy, and we have missed how this shift has laid waste to large pockets of our country. This first wave was a hurricane; the next wave, impacting even more people, may be a tsunami. We believe that the answer to the rising machine intelligence and increase global competition is re-conceived systems of education. These systems need to be rooted in tapping into students’ purpose and instilling an expectation of life long, agile learning with an entrepreneurial outlook that will enable students to continually re-assess changing market realities.

We share this well publicized chart from the Brookings Deaths of Despair research that depicts the dramatic change in mortality rates for white Americans with a high school education or less. We understand the criticism of this potentially flawed research in that it doesn’t compare individuals of different races and the same education levels and, thus, as a comparison may not be as dramatic or alarming as presented.

What is clear, however is that the red line (White, Non-Hispanic, High School or Less) has gone up. The mortality rate for this segment of the population is climbing at a time when we are improving longevity for virtually every other population segment. That is notable.

Conclusion

We need to reframe education and learning. We need to increase access through a combination of technology and cost reductions. But equally important, we need to focus on building self-awareness about skills and aptitudes as well as passion and purpose. We need to establish a national culture of higher levels of educational attainment and continual up-skilling to survive the continual pressures of globalization and automation. We need a more highly educated populace with greater adaptability and learning agility to meet the rising demand for non-routine cognitive work. We need to stop our tug of war with the past, stop blaming immigrants and trade deals, and start focusing on smart systems of life long learning to pull our entire populace up out of despair. Our lives may just depend upon it.

About the Authors

Robert E. Johnson, Ph.D. is the Chancellor of the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth and the former President of Becker College. More information about Dr. Johnson can be found at The Agile Future.

Heather E. McGowan is an academic and corporate consultant who works at the intersection of the Future of Work and the Future of Learning. More information can be found about her work at The Future [of Work] is Learning.