Susan Chubinskaya, PhD

Vice Provost for Faculty Affairs, Klaus Kuettner Professor for Osteoarthritis Research, Professor in the Departments of Pediatrics, Orthopedic Surgery, and Internal Medicine at Rush University Amarjit S. Virdi, PhD

Director of the Office of Rush Mentoring Programs, Associate Professor in the Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology at Rush University

The Challenge

As a private, nonprofit healthcare institution offering certificate, undergraduate (very few), graduate degrees, and postgraduate training, Rush University (RU), an academic arm of Rush University Medical Center and Rush System for Health in Chicago, has almost 2000 faculty, and 52% are women. Since July 2006, we’ve been invested in developing systemic mentoring programs for our faculty, beginning with the Rush Research Mentoring Program (RRMP), which helps early career faculty develop and lead independent, extramurally funded translational research programs. Building on the framework of the RRMP, we’ve subsequently developed other mentoring programs, such as Rush Educational Mentoring Program (REMP), mentoring program for postdoctoral fellows through Rush Postdoctoral Society (RPDS), and, recently, our Rush Women Faculty Mentoring Program (RWMP). All these programs provide tremendous resources to faculty, offer continued education credits, and are optional, though participation in these programs is highly encouraged.

Gender equity and diversity is one of the core values of RU. Women faculty often face unique career challenges and exceptional pressures on their work/life balance. Our understanding of the needs of these faculty at various career stages is evolving with time. In creating the RWMP, we’ve needed to be creative and flexible; it’s critical to revisit our strategies and programmatic developments regularly to ensure they remain aligned with the needs of our women faculty, demands of their jobs and families.

There are a number of key challenges that the development of women mentoring programs at institutions of higher education and in particular, academic medicine, may face. 1) Lack or insufficient buy-in/support from the institutional leadership. This support should be tangible through concerted efforts in allocation of appropriate financial and staff resources. 2) Building comprehensive and sustainable programs requires institutional policies that guarantee work flexibility and protected time for faculty to participate in program’s offerings. This is an ongoing challenge due to specific aspects of academic medicine. 3) The need for a culture change at all levels of leadership to support this approach to career advancement. 4) Program scheduling issues that compete with patient care schedule and other demands; 5) Existing inertia of women faculty, or more broadly, the need to incentivize women mentees and women mentors to participate in the mentoring programs in a meaningful way considering competing demands of family and job-related obligations. 6) Women faculty’s perceptions and often lack of proactive behaviors; and finally, 7) Identification of key outcome measures and metrics of success of such programs.

Here is how we went about establishing our program—and some of the features that keep it effective.

Steps We Took

Initially, prior to launching the RWMP, we conducted the needs assessment of more than 900 women faculty at Rush using a 35-questions survey. We asked about concerns they had with their careers, confidence level regarding general skills, leadership experience, and their willingness to engage with the program as a mentor or mentee. We found that women at the rank of instructor and assistant professor expressed considerable concerns about their chances of advancing within the University, their likelihood of obtaining independent funding, and their ability to meaningfully balance work and family responsibilities. Women at mid-career stage (associate professors and newly promoted professors) were concerned with larger demands of their job, readiness for transition to leadership roles and uncertainty about leadership opportunities. They were also worried about sustainability of their funding, visibility and status within profession and the institution, access to professional development and leadership training, and about next career steps. These findings were consistent with national data (McMurray et al, 2000), in which women faculty members reported lower job satisfaction, less recognition, higher burnout, and fewer opportunities for promotion and career advancement than their male counterparts.

One thing the survey findings made very clear to us was that it wouldn’t be enough to simply provide some basic resources and mentoring at the early career stage. It is essential to understand the needs of women faculty at each career stage, customize and package program’s offerings and support based on an individual’s needs, and support women faculty in their growth and aspirations throughout their career, or as we call it, throughout their “faculty life cycle”: junior (postdoctoral and clinical fellows), early career (instructors and assistant professors), mid-career (associate professors and mid-level leaders), and senior (professors and faculty with higher level leadership and administrative responsibilities). Importantly, we decided to house RWMP within the Office of Mentoring Programs under the umbrella of Faculty Affairs, which allows women faculty to benefit from all of RU’s mentoring, training, and continued education programs and offerings, not only the program specifically designed for women.

We convened a RWMP steering committee, which, in addition to the Vice Provost for Faculty Affairs, College Deans, and the Director of Mentoring Programs, included senior faculty from all four colleges serving as mentors, and a representative from the mentee group. The steering committee provided an input on the vision and mission, short, and long-term goals, design of the program and strategies for implementation and evaluation.

In order to be successful such programs should 1) be mandatory; 2) provide a coherent system of professional development offerings/courses that align with individual needs and career pathways; 3) offer multiple institutional resources and support systems including, but not limiting to pilot grants, consultant services, sponsorship and coaching opportunities, and other; 4) utilize scholarly knowledge base regarding adult learning styles and principles in higher education and academic medicine; 5) nurture a sense of community among female faculty members early in their careers; 6) foster a culture that is conducive to inter-professional collaboration and partnership; and 7) create policies and concrete tools to address inequities in compensation and access to leadership, burnout, wellness, and work/life integration. Activities should include but not be limited to 1) a special on-boarding process for new faculty hires; 2) career planning, e.g., a group boot camp as well as personalized services; 3) facilitated small group sessions and mock study sections to encourage peer support and guidance on project design and scholarly work; 4) educational courses; 5) workshops and seminars on relevant topics, e.g., “Parenting for Dual-Career Couples”; 6) one-on-one coaching and mentoring; 7) retreats, networking, and social events; 8) assistance with the academic promotion process; and 9) internal and external professional development leadership opportunities.

Similarly to what was published by Kashiwagi et al (2013) about key elements of successful mentoring program, the initial components of our program included resources (in addition to those available through other RU mentoring programs, financial support for professional and leadership development, one-on-one coaching consultations, promotion guidance), pair-mentoring, peer-mentoring, an oversight committee, seminars/workshops, and networking and social events. The mission of our program would be to provide comprehensive mentoring, sponsorship, and support to women faculty within a nurturing, engaging, and empowering environment. The long-term goals of the RWMP are to improve retention of women faculty, increase engagement and satisfaction with their career pace, and to establish a pipeline of women leaders. Based on the results of our survey, we identified a number of mentoring tracks that helped us to match the needs, interests, and personalities of mentees with mentors: a) Research, in which women faculty expressed an interest in individualized research mentoring; b) Education, in which women faculty needed help with their educational competencies and knowledge of key teaching principles and philosophies; c) Academic promotion, the need for help with getting ready for promotion to the next rank; d) Professional needs associated with mid-career stage; e) Navigation through Rush culture, this was specifically important for newly hired faculty; f) Leadership competencies and leadership development.

We created a document that defined expectations from both parties involved (mentees and mentors), the term and length of these structured mentoring relationships, and an agreement on how these relationships will be initiated and maintained. We also asked mentees to define their goals, timeline, and key milestones. For example, mentees were expected to be proactive in initiating the meetings and developing an agenda for each meeting with the mentor; mentees and mentors were expected to decide on frequency and mode of interactions. Every six months, we surveyed mentees and mentors regarding their satisfaction with the quality of mentor-mentee relationships, progress towards defined goals, and additional needs or changes. We also had a couple of cases that required a change in assigned mentor and/or addition of a second mentor. To complement the formal mentoring experience, we also organized opportunities for peer mentoring, in which mentees learned from each other. Further, as part of this program, twice a year we offered a social “Wine and Cheese” get-together reception (also called a speed mentoring event) with the goal of providing an opportunity for all women faculty to meet each other, learn about RWMP, and get engaged with the program.

The most popular activity of RWMP was an informal networking event called “Breakfast with Vice Provost” that occurred every last Friday of the month at 8am. We either held informal conversations on topics suggested by women faculty (weight loss experience and diet, work/life integration, childcare, elderly care, an interesting book they read, hobbies, etc.) or invited accomplished Rush leaders— women and men, to share their pearls of wisdom, discuss their career trajectory, role of mentors in their own career successes, and how they pay it forward by mentoring others. Through these breakfasts we were able to create a safe, friendly, and informal environment, in which our women faculty felt comfortable to open up and discuss any challenges they were experiencing, seek advice in difficult personal or professional situations, and learn that they are not alone and that many of us were in similar situations. Importantly, such an informal platform also allowed newly hired women to meet other women, learn about the organization, and build relationships, collaborations, friendship, and a network of their peers. Since these breakfasts were advertised across the entire institution, they brought a very diverse group of participants, including faculty, staff, students, residents, and fellows. An average number of participants ranged from 30 to 100 people.

Impact and Further Development of the Program

In this way, we created the first iteration of what we hoped would become a comprehensive mentoring program that would provide women faculty with resources, mentors, and critical networking opportunities throughout the stages of their faculty career. But how would we know if these efforts were having an impact and how should we adapt the program to our new pandemic reality?

In assessing whether RWMP was making an impact, we realized that the major challenge is to define metrics of success. It is much easier to develop quantitative outcomes to measure the success of the research mentoring program (for example, the number of grants, amount of extramural grant funding, number of peer-reviewed publications, and other) than that of RWMP, since multiple factors, personal and organizational, influence career progression of women faculty. We were not convinced that satisfaction of participants with the program was a sufficient metric.

After running the program for 5 years, we decided to perform a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis and re-visit our strategies and tactics, reviewing how to build on our successes, address shortcomings, and most importantly, remain relevant and continue to add value. This coincided with the expansion of the Office of Faculty Affairs through a creation of the Center for Innovative & Lifelong Learning (CILL). This Center offers a wide variety of continued education options, including license-specific, professional and leadership development learning and training opportunities. The addition of such a unique resource with highly regarded experts in professional and leadership development greatly expanded our resources and offerings. Almost concurrently, this coincided with COVID-19 pandemics that not only changed the way we lived and worked, but also forced us to think out of the box, adapt to virtual reality, develop new approaches to education (including professional and leadership), and accept and adjust to new organizational structures, cultures, financial models, professional and personal demands.

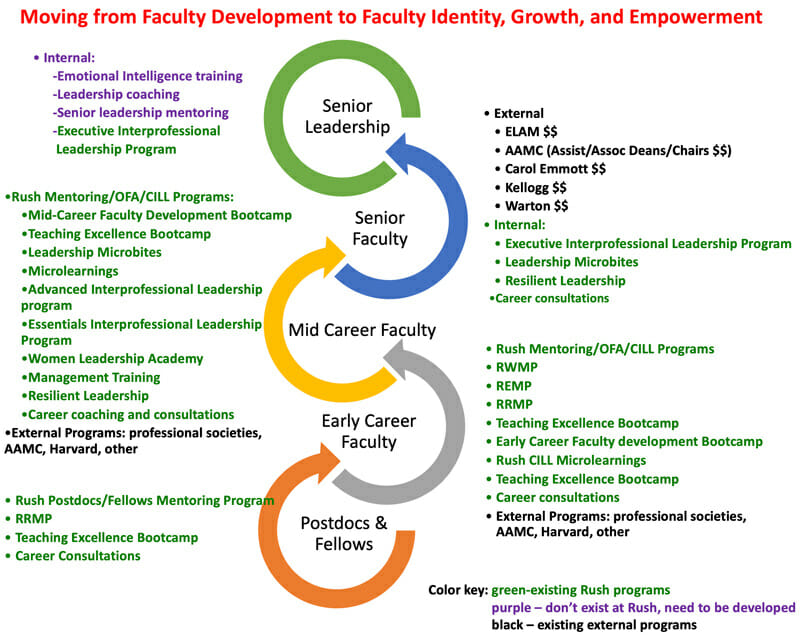

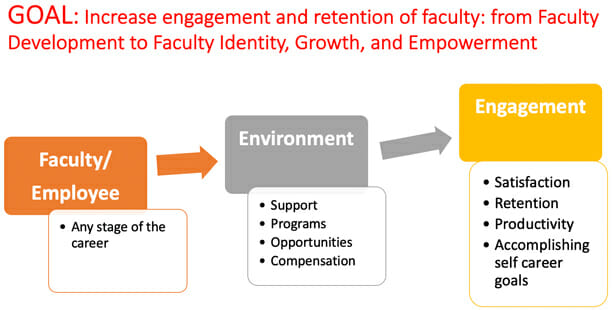

Currently, we are in Phase II implementation of RWMP. We are creating a model of personalized mentoring tailored to each woman faculty member’s career aspirations throughout their faculty life cycle. We want to support women faculty members’ professional and career development as soon as they join Rush and then at each stage of their careers. You can see a schematic depiction of this program in Fig.1. We identified the reasons for talent loss, gaps in existing support of faculty career advancement, internal offerings including available resources, and external resources available to our women faculty through various professional societies and organizations. This helped us to stay focused and be strategic in addressing the gaps and investing human and financial resources (Fig 2).

Figure 1. Schematic depiction of Rush Women Mentoring Program (RWMP) Goals.

Figure 2. Concept of Individualized and Targeted Faculty Development in Academic Medicine. This approach can be utilized for women faculty mentoring as well as provide a framework for faculty mentoring in higher education. Abbreviations: OFA, Office of Faculty Affairs; CILL, Center for Innovative & Lifelong Learning; AAMC, Association of American Medical Colleges; RILP, Rush Interprofessional Leadership Program; RRMP, Rush Research Mentoring Program; REMP, Rush Educational Mentoring Program; RWMP, Rush Women Faculty Mentoring Program; ELAM, Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine offered by Drexel University. The title of this figure refers to editorial in Academic Medicine3

To provide this kind of support, it is critical to establish an individualized learning and career development plan. During pre-employment onboarding, women faculty, regardless of their career stage or academic rank, are informed about programs, resources, and opportunities available at Rush. Then they meet with the Vice Provost for Faculty Affairs and the Director of the Office of Mentoring programs to discuss their career aspirations and specific mentoring needs. Subsequently, together with their supervisor/department chair, women faculty are expected to create an “individual development/career advancement plan”, which should be regularly reviewed, at least during an annual performance evaluation since such plan becomes part of their annual professional development and leadership development goals. By the way, this same approach is equally applicable to men faculty.

Below are examples of how personalized mentoring is provided to women faculty at each stage of their careers:

Postdoctoral researchers and fellows join the Rush Postdoctoral Society upon arrival to Rush. They are expected to enroll in the online research training course facilitated by weekly face-to-face meetings. They participate in grant writing and career development courses (including the creation of individualized research developmental plans), utilize editing and statistical services, and are eligible for philanthropic pilot grants and career development grants. They also participate in teaching academy, teaching excellence bootcamp, multiple workshops, seminars, and early-career faculty development bootcamp.

Early career faculty (instructors and assistant professors) dependent on their interest, roles, and allocated time for each role, join either the RRMP or the REMP, in addition to the RWMP with the opportunity to benefit from all resources provided through these programs. They are eligible for philanthropic pilot grants and participate in internal and external professional development workshops, early-career faculty development bootcamp, and in a number of continued education programs relevant to their career goals offered by CILL. Mentees in the RRMP are also eligible for applying to Cohn Fellowship that is specifically aimed at providing support to secure protected time for research: basic, clinical or educational. They are also guided through one-on-one consultations on the career advancement including promotion to Associate Professor.

Mid-career faculty (associate professors and mid-level leaders: section/division chiefs, clerkship, and program directors) continue to receive resources and mentoring to maintain scholarly productivity and achieve their career goals. They work with the Vice Provost on their promotion to professors and career advancement and are sponsored to participate in various internal and external leadership development programs, for example: mid-career faculty development bootcamps, resilient leadership, Interprofessional Leadership Program, Women Leadership Academy, programs available through professional societies and associations. Important to mention, that all Rush professional and leadership development programs offer continued education credits.

Senior faculty are continued to be supported in each area of mentoring, in addition to full support for participation in internal and external senior leadership training including AAMC programs for Assistant/Associate Deans and Department Chairs, ELAM, Carol Emmott fellowship, Harvard, Kellogg, and Warton leadership courses. Since external senior leadership development programs are very expensive and limit the number of participants, we created a three-tier Rush Interprofessional Leadership Program (Essentials, Advanced, and Executive) to specifically address the needs of senior women faculty.

The following are some program accomplishments to date:

- 64 women attended AAMC/Harvard/other external professional development programs sponsored by the Office of Faculty Affairs

- 94 of RRMP women faculty participants stayed at Rush (65%)

- 21 women faculty (out of 35 or 60%) are recipients of internal Cohn Fellowship pilot grant available only to mentees of RRMP and REMP

- 85.7% of Women Cohn Fellowship recipients stayed at Rush post award

- 112 women faculty participated in mentor-mentees pairs in the RWMP

- Since 2015, 1938 women from RWMP attended workshops/seminar series

- Since 2018, 218 women faculty attended newly developed early career and mid-career professional development seminars at Rush

- Since 2014, 132 women faculty attended Teaching Excellence Courses/Bootcamps

Though mentorship and peer-to-peer support programs for women exist at multiple higher education institutions, including academic medicine, women need intentional leadership training. Therefore, we believe that sustainable, dedicated to women faculty, and targeted and individualized mentoring throughout the entire career is paramount to the advancement of women because historically primarily only men have been provided access to the formal and informal opportunities to learn and cultivate leadership skills. And finally, it is important for the academic institutions to address mentoring as a core responsibility with defined relevant and specific metrics of success.

Concluding Remarks

In summary, it is imperative that women faculty, including physicians, establish strong mentorship relationships throughout their professional careers. The creation of a targeted and individualized women faculty mentoring program that addresses their needs throughout the entire faculty life cycle should encourage senior women faculty, and men, an opportunity to provide valuable guidance and direction to junior women faculty with regards to clinical, education, research and administrative advancement. In the promotion model for our institution, success in all of these missions is critical for women to reach career milestone. Such a program should also help our women faculty identify strong mentors, build their academic portfolios and develop leadership skills while opening doors for advancement. A mentoring program like this, and relationships built, would allow women faculty not only career guidance, but also create a safe place for them to discuss pay inequities, microaggressions and sexual harassment. On a flip side, through an offered concept of continuing mentoring, senior women faculty would find additional opportunities for their own professional and leadership advancement because being a mentor and a mentee at the same time provides additional understanding of and perspectives on fundamental concepts of leadership.

We would like to thank the RWMP Steering Committee for their guidance, and mentors and mentees for making the program a success. We would also like to thank Dr. Giselle Sandi, former director of the Office of Mentoring Programs, for her contributions to the establishment of RWMP.

Work Cited

Editorial. Moving from faculty development to faculty identity, growth, and empowerment. Acad. Med.2016;91:1585-1587

J E McMurray, M Linzer, T R Konrad, J Douglas, R Shugerman, K Nelson. The work lives of women physicians results from the physician work life study. The SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group. J Gen Intern Med. 2000 Jun;15(6):372-80

Kashiwagi DT, Varkey P, Cook DA. Mentoring programs for physicians in academic medicine: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;88: 1029–1037.

Dr. Susan Chubinskaya is an internationally recognized expert in the field of cartilage repair/regeneration. In her role as Vice Provost, Susan oversees Faculty Affairs, Faculty Development, Office of Mentoring Programs, Office of Global Health, and the Center for Innovative Lifelong Learning. She is the recipient of the Orthopedic Research Society Women’s Leadership Forum Award and the Orthopedic Research Society Presidential Award. Her work in Faculty Affairs was recognized by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) by awarding her office with the 2019 Group on Women in Medicine and Science (GWIMS/AAMC) Leadership Award for an organization.

Dr. Susan Chubinskaya is an internationally recognized expert in the field of cartilage repair/regeneration. In her role as Vice Provost, Susan oversees Faculty Affairs, Faculty Development, Office of Mentoring Programs, Office of Global Health, and the Center for Innovative Lifelong Learning. She is the recipient of the Orthopedic Research Society Women’s Leadership Forum Award and the Orthopedic Research Society Presidential Award. Her work in Faculty Affairs was recognized by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) by awarding her office with the 2019 Group on Women in Medicine and Science (GWIMS/AAMC) Leadership Award for an organization.

Dr. Amarjit S. Virdi is the Director of the Office of Rush Mentoring Programs that includes Women Mentoring Program. He is also an Associate Professor in the Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology at Rush University.

Dr. Amarjit S. Virdi is the Director of the Office of Rush Mentoring Programs that includes Women Mentoring Program. He is also an Associate Professor in the Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology at Rush University.