The recent Sweet Briar crisis highlighted the difficulties that at-risk institutions face in ensuring their basic survival. Not only has the feasibility of a women’s college been questioned, but also the viability of small colleges in general. Often, colleges respond to difficulties with incremental improvements and enhancements — short-term remedies that tend not to address the fundamental issues; stories about substantive change are harder to find.

What are proven ways for a president to lead an at-risk institution back to long-term, sustainable financial health?

Answers were to be found at a recent Academic Impressions conference, “Foundations for Innovation at Small Institutions.” (You can read the paper that sparked this conference here.) The conference featured presidents of relatively small institutions who have led quite amazing turnarounds. I will share some of their stories — and insights that can be gleaned from them — below.

A Diagnosis: What Makes the Small College Turnaround Difficult?

Yet these turnarounds tend to be the exception rather than the rule. Why are so many at-risk institutions slow to react to their situation?

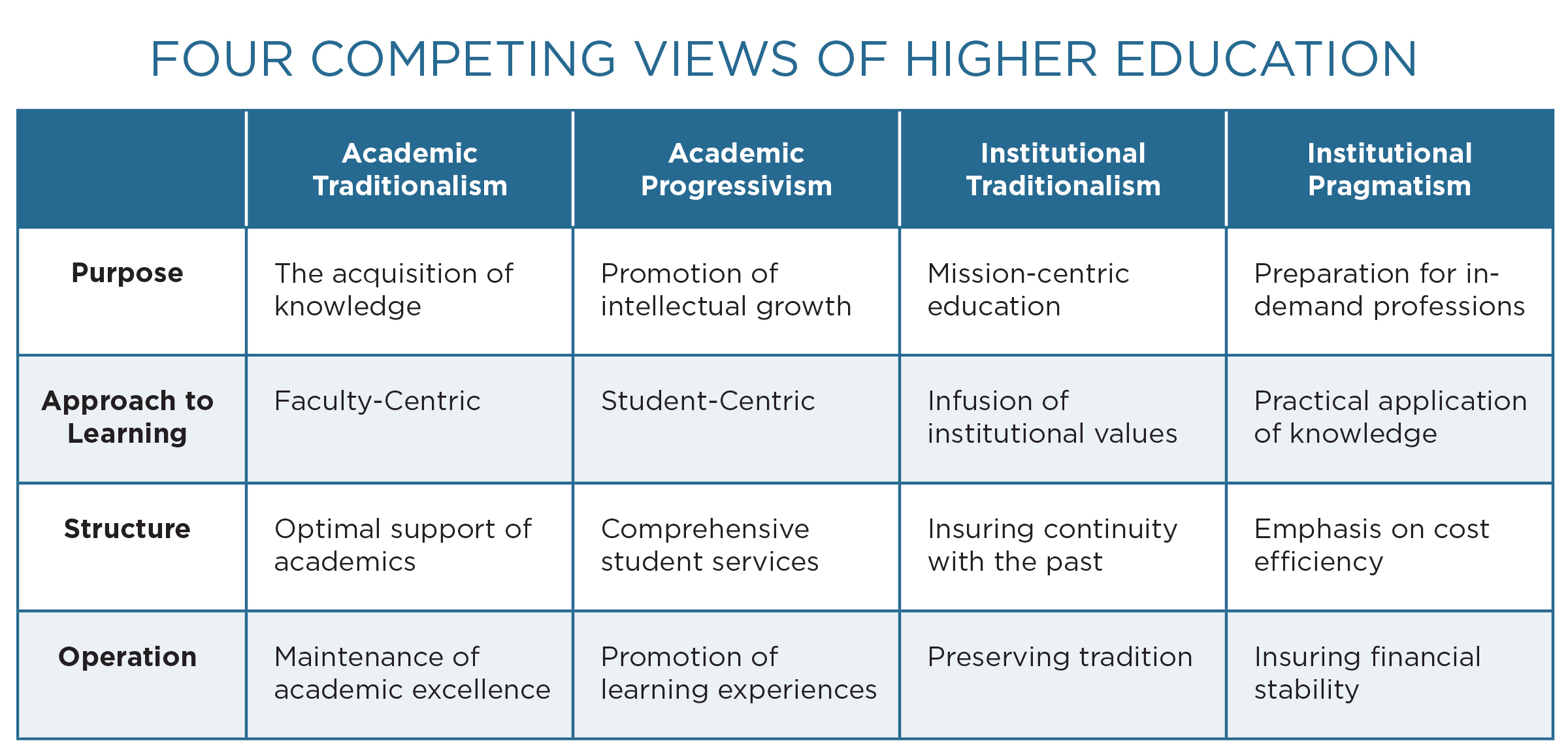

The answer is that there is a clash of worldviews within the university, all competing for influence over the institution’s direction:

- Academic traditionalism, which sees college as a rigorous immersion into the intellectual world of the disciplines. In this view, the quality of faculty research and teaching determines the reputation of the institution.

- Academic progressivism, which tends to emphasize students’ intellectual growth. The university’s reputation rests upon how well it helps students use newfound knowledge to solve individual and social problems.

- Institutional traditionalism, which embraces the specific mission of the university as its contribution to higher education and society at large. Success is measured by how well alumni(ae) embody its institutional values in their professional and personal lives.

- Institutional pragmatism, which recognizes the reality that students attend a university primarily to prepare for an in-demand profession. In this view, a university’s reputation rests upon how it contributes to developments in the professions so that its students are properly prepared for a successful career.

It would be a mistake to associate a worldview solely with one particular group within the university community. Not all faculty members are traditionalists, and not all administrators are institutional pragmatists. This reality makes differences in worldview all the more difficult to negotiate. It is for this reason that some presidents who are recruited from outside of higher education have difficulty navigating troubled waters. Often it is presumed that business experience or political acumen can bring an outside perspective to solve problems, but there is no substitute for deep knowledge of the assumptive worlds that are held by members of the university community.

Likewise, new presidents who have spent their entire professional lives in academia may assume most people in the institution hold their worldview, or it is the only one that can right the financial ship. Acknowledgment of good-willed but different conceptions of the nature of the university is a necessary ingredient for sound leadership. But melding differences into a consensus worldview is highly unlikely to work and is a singularly bad idea.

The Kind of Leadership Small Institutions Need

Navigating these tensions requires adept leadership, particularly for financially at-risk institutions.

After hearing from presidents at the Academic Impressions conference, I was able to identify a change process that these successful leaders put into effect at their institutions. This process involves more than applying certain techniques or strategies. To effect change, small college leaders need to:

- Expose “what is” and build trust.

- Articulate “what could be” and foster creativity.

- Choose “what should be” and share power wisely.

- Lead change courageously toward “what will be.”

Doing this requires leaders who can galvanize the goodwill of university community members who hold very different worldviews. This change process is particularly useful, if not crucial, to leadership in vulnerable institutions. Let’s look at real-world examples of each of these four steps.

1. Expose “What Is” and Build Trust

Good leaders engender trust by honestly and carefully presenting the financial and structural problems of an institution. This helps the university community to see the extent of the problem, exposing what the situation actually is.

EXAMPLE:

G.T. “Buck” Smith, president emeritus of Chapman University tells a story about the first week of his presidency in 1977. The LA Times had just published an article indicating that Chapman might close because of the deteriorated state of its campus and its mounting debt. President Smith met with the chair of the Board of Trustees, with the article in hand. The university’s amazing turnaround began with a clear, concrete wakeup call.

Clarity and transparency enable the university community to trust its leadership. Not everyone wants to shake up the status quo. But confronting problems head on is the first step toward positive change.

2. Articulate “What Could Be” and Foster Creativity

When the details of a university’s financially at-risk status are made clear to the campus community, that sets the stage for the second movement in a change process—articulating “what could be.” Creating an open moment for creative change requires that leaders communicate a genuine openness to credible ideas for transformation and that they invite ideas from stakeholders throughout the community.

EXAMPLE:

Arthur Kirk, President Emeritus of Saint Leo University, recalls his first few weeks on the job in 1997. His first order of business was to make the University’s dire financial situation clearly evident. Then the question was what to do next.

What they did next was creative and risky. Kirk led the university into the emerging online degree movement. As one of the few nonprofit universities in the market, Saint Leo grew exponentially, while at the same time enhancing the on-campus experience of traditional students. Today, Saint Leo is one of the largest Catholic universities in the United States. That wouldn’t have happened without creative problem-solving at the crucial moment.

3. Choose “What Should Be” and Share Power Wisely

The third step in moving an institution from unsustainability to viability is to choose the right course of action—”what should be.” A small group of leaders from across the university who have the good of the whole institution at heart can work with a president to assess the alternative futures that the university might pursue, and make the right choice.

This small, diverse group is crucial. Leadership is not a singular endeavor; leaders need followers in order to be successful. And followers need to be encouraged into future leadership roles for the continued progress of the institution.

EXAMPLE:

Gary Brahm held various leadership roles at Chapman University prior to becoming Founding Chancellor and CEO of Brandman University. Brandman grew out of Chapman University College becoming its own fully accredited university, thereby creating the Chapman University System.

This structural innovation (creating a university system out of a single university) was one of several options for how Chapman might grow its capacity for serving non-traditional students. The bold move to create Brandman University — giving Brandman the unfettered ability to innovate with new approaches — came out of sound analysis by the Chapman leadership team. And the decision has proven to be the correct one.

Under Chancellor Brahm’s leadership, Brandman now has over 25 extension campuses in California and Oregon serving over 7,500 students in associate’s, bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees. Most of its degree programs are offered in a blended format (partially online and partially in the classroom), with fully online degree options offered as well.

4. Lead Change Courageously Toward “What Will Be”

Once the process of transformative change has begun with the articulation of a university’s financial at-risk situation and with cogent analysis of possible alternative futures, it is crucial that a president act decisively and courageously to guide the institution along the chosen path forward. One way to overcome the initial misgivings of those who fear a change in the status quo is to communicate an exciting future effectively.

EXAMPLE:

The Saint Leo University turnaround started with then-President Kirk’s request to the Board of Trustees for an additional $600,000 to start an online program division. The Trustees, and the university community in general, could not conceive how Saint Leo’s precarious budget could support the expenditure. President Kirk cobbled together funds from unused elements of the university’s balance sheet and started in earnest.

The President’s decisive move animated the university community into action. In effect, the president put his position in jeopardy both to emphasize the value of pursuing new directions and to model action based on courage of conviction. Because of these types of initiatives, Saint Leo’s net assets moved from $19 million in 1997 to over $175 million today.

Conclusion: Creating the Transformative Moment

The endemic clash of worldviews on U.S. college campuses today is not new. That type of creative tension has always been a part of university life. At times, it makes a university vibrant and alive. But it can also keep universities trapped in inaction, especially when the reality of financial instability becomes apparent.

It takes a transformational leader to help an institution seize its transformational moment. Leaders need to avoid being mired in negotiating competing worldviews. Helping a university overcome internal dissonance to create a transformative vision of “what will be” is a great act of leadership. And institutions become great when they create a sustainable future that lives up to their noblest aspirations and values.

Preferred Citation: Dumestre, Marcel. “The Transformational Small College President.” Higher Ed Impact. Academic Impressions, December 10, 2015. www.academicimpressions.com/news/transformational-small-college-president.