also by Alan Ritacco

(Learn more in the recorded webcast: The Future of Work and the Academy)

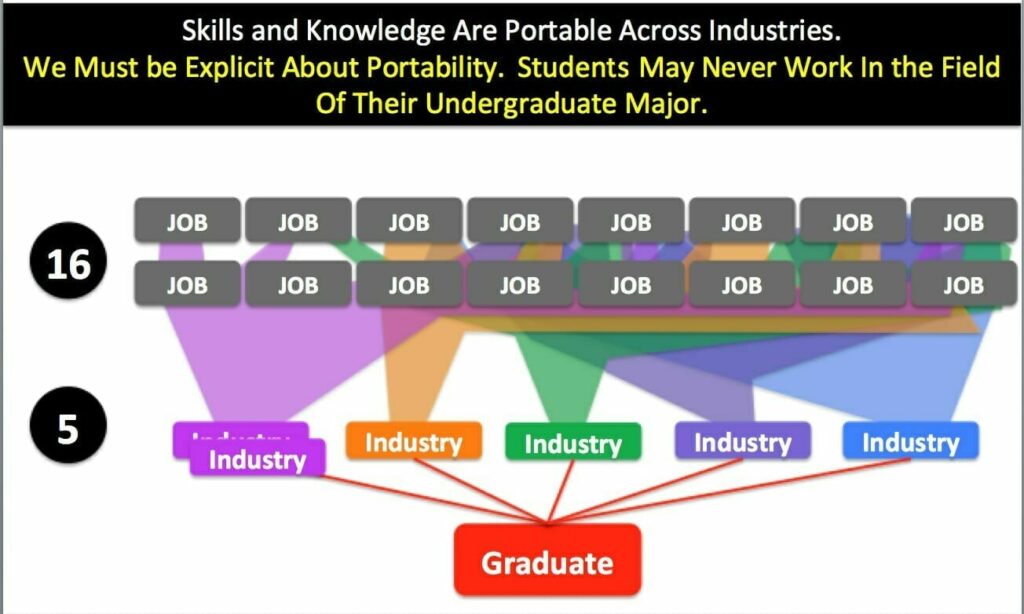

Abstract: A recent study reveals that young people today could have as many as 16-17 different jobs in 5 industries.

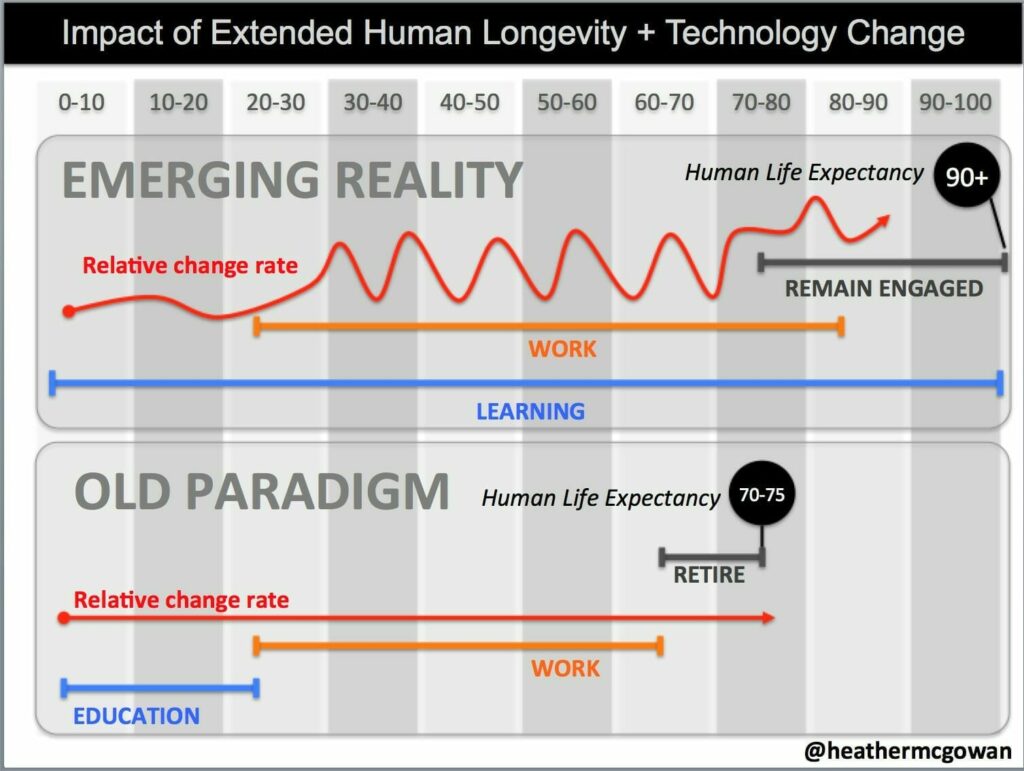

As the rate of technological change becomes exponential, the future of work requires adapting to change, recognizing job failure as a norm, and (since we are living longer) a longer career arc in which to experience many different and uniquely distinct careers.

Are most institutions of higher education preparing students for this reality?

According to the recent report by the Foundation for Young Australians, The New Work Mindset (a study built upon the Future of Work research studies of both the McKinsey Global Institute and the World Economic Forum), young people today could have as many as 16-17 different jobs in 5 industries:

And considering that the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that there are more than 1.5 million involuntary and 3 million voluntary separations per month, the fact is: job loss and job change are a norm. Job change, whether voluntary or involuntary, is part of having a professional career. As higher education professionals, we prepare students for their first professional jobs. We, as an industry, should prepare students not only for their first jobs, but also to make jobs, and to adapt and reinvent themselves when they lose their jobs.

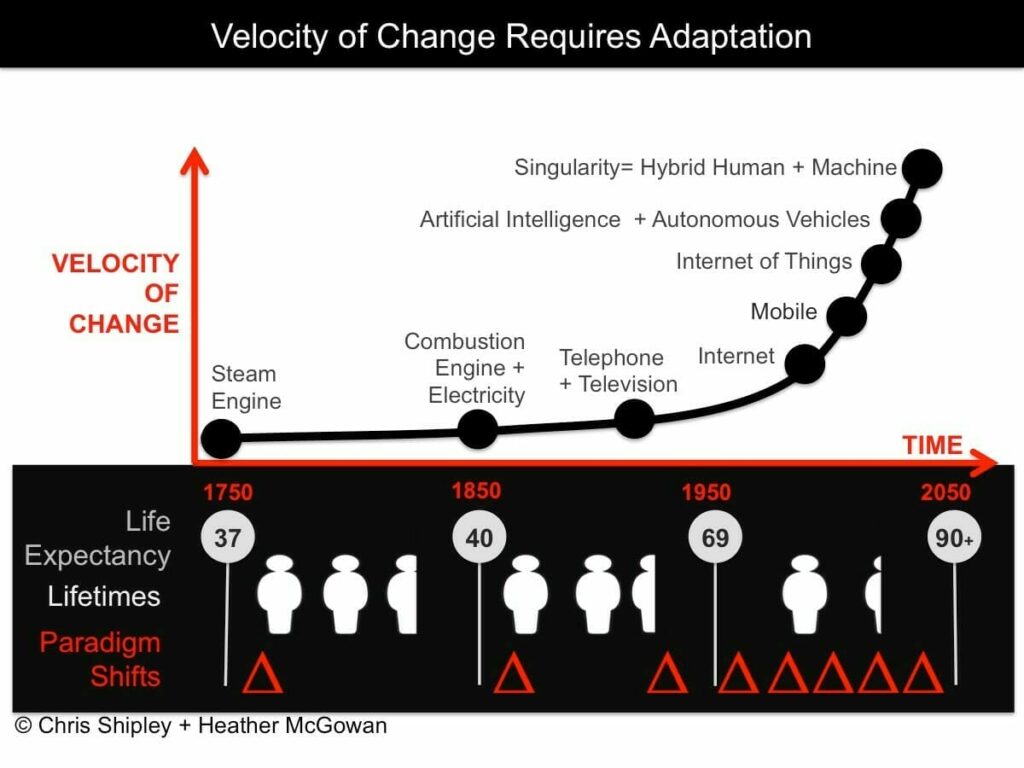

According to futurist Ray Kurzweil, who has made 147 predictions about technology with an 86% accuracy rate, we will not experience 100 years’ worth of progress in the 21st century. Instead, we will see the equivalent of 20,000 years of change and advancement (at today’s rate), due to exponential growth in computing power. A report by Deloitte University Press on the impact of this accelerating change predicts that 50% of the content in an undergraduate degree will be obsolete within five years. NYT Columnist Thomas Friedman has summed this situation up: “Anything mentally routine or predictable can and will be achieved by an algorithm.”

As a result of these forces and emerging realities, whereas productivity shifts were once absorbed across a lifetime, allowing workers to adjust at pace, these shifts are now occurring on an exponential growth curve, where change whipsaws workers from job to job, from employer to employer, career to career. In this reality, learning and adapting become the only constants. The future of work is adapting to change, failure as a norm, and (since we are living longer) a longer career arc in which to experience many different and uniquely distinct careers.

Are most institutions of higher education embracing this reality?

Change as a Norm: The Agile Mindset

Where we work at Becker College we have crafted an institutional ethos focused squarely on this reality. We assumed frequent industry disruption cycles, and we asked: How do we help people continually adapt to change, develop the ability and agility to learn continuously throughout their career arc, and instill an entrepreneurial outlook so they continually seek to create new value for themselves and the entities for which they work?

The agile mindset focuses on cultivating adaptive learners who can leverage the uniquely human skills of:

- Empathy to find new needs

- Divergent thinking to find and frame problems not yet known

- An entrepreneurial outlook to turn discovered needs into sustainable value, and

- Social and emotional intelligence to adapt and thrive in a world that is increasingly volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous.

With rising computerized automation replacing repetitive and routine work, expanding cognitive augmentation of the professions, and a rapidly swelling global workforce, the future of work is going to be a minefield of change and adaptation. Essential to this new norm is establishing greater self-awareness, managing self-doubt, and developing confidence even in times of uncertainty and ambiguity. This is as much a development of the social self as it is the intellectual self. We believe we must develop the whole student.

The Empathy Imperative

In this new academic foundation, we have an explicit focus on empathy. The World Economic Forum recently declared empathy “the one crucial skill our education system is missing.” We use empathy to understand and connect with other individuals and populations—an especially important concept now that we live in a hyper-connected, multicultural, global society. In fact, we use empathy in most business decisions, or should, so that we are targeting the correct audience and addressing the needs of the consumers. Empathy is considered by many to be the essential catalyst for consumer-focused innovation—delighting the customer by meeting their needs better than anyone else. There is another, and perhaps more important, role for empathy—empathy for yourself.

The Continuous Reinvention of Self

We have a colleague who says “I find it difficult to work with people who have never been through job loss or similar, unexpected, major change.” We have explicit conversations about this. Whenever we interact with people who have only had one job or only one context and only one culture, they are often resistant to change, a bit more calcified in their mindset, and limited in their ability to adapt. Indeed, a study by Harvard Business Review found that immigrants are more entrepreneurial—in part, they theorize, because immigrants are superior at recognizing and shaping opportunities, because they view potential value from more than one cultural perspective. Further, as immigrants have often endured more hardships, they have more persistence and greater ability to move past and through failure to adapt and persevere.

Being separated voluntarily or involuntarily—or other major “failures”—requires an individual to process stages of grief, to be self-reflective, and to forgive themselves and to pick themselves up. They have to recast themselves, making sense of and most likely spinning their story so that they can march back to relevance—after being told, in some form or another, that their value was not necessary to the entity. That reinvention is going to be predominant in the future of work, and developing the grit to have empathy for yourself and to manage your internal negative critic will separate those who are successful in the future with those who struggle. Going through this reinvention process will involve stages of grief, as shown below:

Empathy for oneself is a form of NVC (non-violent communication) and was developed by Marshall Rosenberg as a “state of compassion when no violence is present in the heart.” In a nutshell, everything, in general, tends to move towards a state of equilibrium, and those who can find internal and external solace can reach a state of harmony. Empathy is a judgment free zone that we create for ourselves to evolve from. This is the essential first step in self-reinvention.

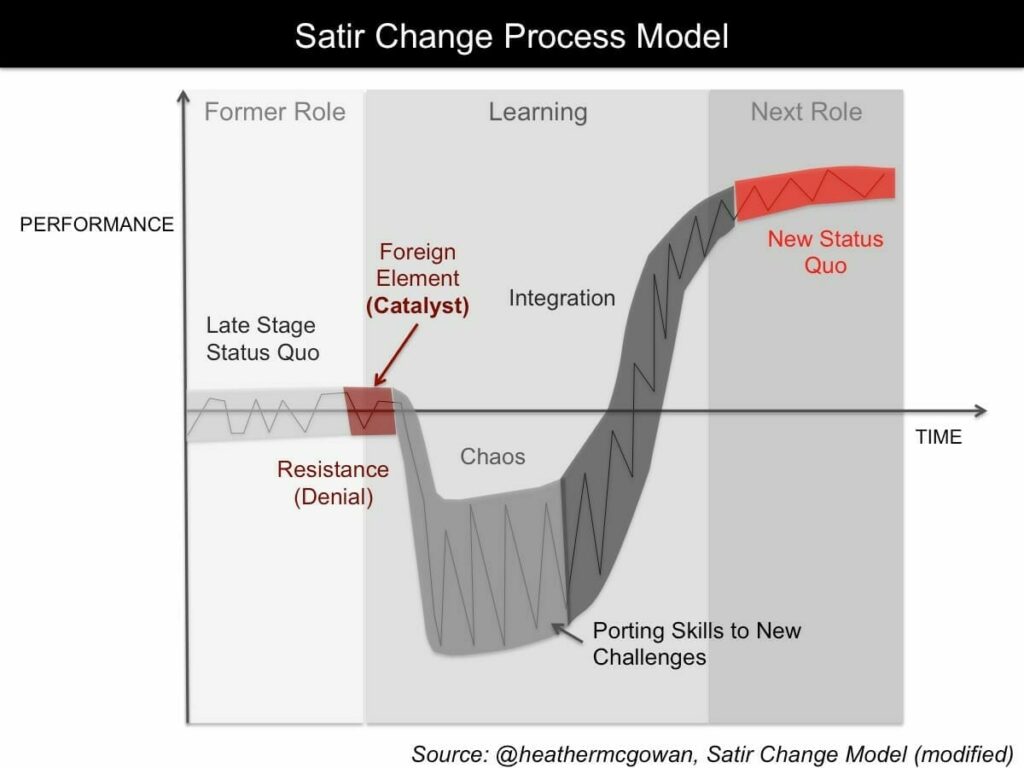

Change Processes, Failure, and Learning

This type of education that we espouse goes beyond the mere consumption of existing knowledge and the acquisition of predetermined skills. It is inquiry and discovery-based learning, fraught with ambiguity and uncertainty. To get through this much change and persevere, one must allow oneself to go through many change processes (see the Satir graphic below) and must process (quickly) many stages of grief when working through the inevitable failures of this type of learning. Without going through these permutations, deep learning and personal evolution will not occur.

Your Thoughts Are Your Destiny: Don’t Believe Everything You Think

How does one explicitly manage these change processes? You can start by not believing everything you think.

We all have thoughts that crop up, positive and negative, and we all ruminate from time to time on these thoughts. Why do we have these thoughts? It has been conjectured that these thoughts and the reason we have them are relics from the past to make sure we are safe—so that we would steer clear and not be eaten by a saber-tooth tiger or just walk in front of a moving car. We need to keep in mind that not all fears are bad, and in fact, they can keep us in check and they are an integral part of self-awareness. One must reflect and realize that negative thoughts beget negative thoughts, and positive thoughts beget positive ones. It is the judgment-free zone that allows one to be freed from the negative thoughts and to begin to focus on the positive ones, so that we can think clearly about how to apply our skills and abilities to new challenges.

It can be easier to have empathy for others, but when it comes to our having empathy for our own thoughts, we tend to be much more critical. Why is that? Well, as the old saying goes, “no one can beat us up like we can.” When we have thoughts that are critical in nature, we need time to reflect upon them and ask “Why we are having these thoughts?” Self-doubt, anxiety, and insecurities emerge in common thoughts such as:

- I cannot do that because I am not smart enough.

- What if I try and fail?

- Look at how easy it was for that other person to do that – why can’t I do that?

- My boss always picks that person and never me; I must not be that smart or important.

Some tips that have been found to help with the concept of “Don’t believe everything you think” include:

- Create a judgment-free zone where you can internally express your thoughts, without shooting them down due to pre-learned actions.

- Ask: Why am I having this thought? Why now? Where did it come from?

- Ask: Is this a “real” thought based on concrete information, or am I being prophetic?

- Ask: Is this me projecting this thought, or is this thought based on concrete evidence?

- Meditate for 15-30 minutes every morning.

- Focus on a certain time of the day in which you will only think of the thoughts that have plagued you in the past. You can call this your ruminating time.

Conclusion: Empathy Begins Within

Change is a norm. It has always been true, but this will absolutely be the hallmark of this next generation. We must continue to prepare graduates with specific skills and expertise to contribute to our global society. But as part of that preparation, we must acknowledge that integral to those contributions will be continuous change—requiring learning from failure, adjusting expectations, persistence, and a great deal of empathy for oneself. With a reality of potentially 16 or 17 different jobs across five industries in a longer career arc marked by the greatest velocity of change in human history, we must begin to develop young people resilient at redefining themselves, learning for life, and at being adept at both creating new jobs and adapting to the inevitability of job loss and change.

Reflections from the Field

We spoke with stakeholders at two institutions that have explicitly created new curricula or experiences designed to prepare students for continuous change and adaption:

“At Philadelphia University, in 2008, we saw these changes and we embraced a similar version of this vision. We created an institutional ethos and related curriculum that embraces continuous learning, adaptation as an expectation and collaboration across disciplines as a norm. The process was a unique yet challenging professional experience for my administration and our faculty, and the result is both high student engagement and employer enthusiasm.”

Dr. Steven Spinelli Jr., PhD., President of Philadelphia University

“I have been teaching English/humanities at my institution for 37 years. As of late we have begun to worry that robots would be taking over our jobs. I realize now, ironically, that if we continue to focus on transferring skills and existing knowledge into our students we are ourselves becoming robots. We cannot ask our students to adapt to change and learn continuously if we do not. We need to exercise the Agile Mindset [adapting to change and learning agility] on a regular basis to keep our unique skill set one step ahead of the robots. We must focus on developing uniquely human skills and an inquiry mindset so that we deliver value that a robot cannot, and so that we create students predisposed for life-long learning, with adaptability to complement rather than compete with rising automation. This process has been unique, and honestly at times difficult as we navigated ambiguity. Ultimately it was incredibly rewarding. It has been the shot in the arm that I needed. I am excited about teaching again after almost four decades.”

Daryl Statkus, Associate Professor of Humanities, Chair of Agile Mindset and Core Curriculum, Becker College

“At PhilaU the faculty had a long tradition of collaboration outside of their discipline for research and teaching; it was in their DNA. The challenge for Academic Affairs was to create a deliberate, organized, and sustainable ecosystem and infrastructure that would focus, support, and incentivize this. This starts with a strong public commitment from the President, Provost, and Deans. We were able accomplish this with the Design, Engineering, and Commerce curriculum (DEC) and our Nexus Learning pedagogy (defined as Active, Collaborative, Real World, and Infused with the Liberal Arts) through a system that included: courses releases, stipends, faculty development opportunities through a new, resourced Center for Teaching Innovation and Nexus Learning, Nexus Learning Grants that support collaboration, Nexus Learning Awards that celebrate collaboration, and a matrix organizational structure with Faculty Nexus Learning Advocates in each college that would encourage and support collaboration. We also incorporated these factors into our evaluation and assessment systems, making them components of the Annual Faculty Activity Reports, Annual Dean’s Evaluation, and assessment reports.”

Dr. Matt Dane Baker, Provost & Dean of the Faculty, Philadelphia University

“The new Agile Mindset core curriculum at Becker College has taught me lessons that I never knew needed to learn. Like most things, you get out of it what you put into it.”

Josh H, Freshman Student, Game Major, Becker College

“The Agile Mindset core courses that I took, I think, are really about finding who you are and the process of finding your place in the world.”

Mack F, Transfer Student, Psychology Major, Becker College

“Change is hard. Managing programmatic change in higher education can be unbelievably difficult and marred with cultural and academic nuisances that can drag the process on indefinitely. Trying to institute a major change and do it quickly can be insurmountable. I’ve worked in small private institutions my entire career and have witnessed the frustrations and challenges that can accompany attempts at substantial change. After years of instability and challenging economics, with a population struggling to meet the demands of college-level work, (now former) President Robert E Johnson, PhD., stepped in at Becker College to change the culture, to change our direction, to change our future. His vision and commitment, and the hard work of faculty have resulted in a core curriculum dedicated to creating agile learners. Students learning how to learn, and being able to reinvent themselves in our ever-changing world filled with only one certainty – that change is inevitable and happening faster than ever before in our history. I was in the dual roles of Chief Academic and Student Affairs Officer at the time. We had to be unified in our leadership and consistent in our vision. We have some incredible faculty members who have stepped up to lead the charge to create something unique to help our students be distinctive in a work landscape that is unlike any we’ve seen. Not everyone was on the bus when we started driving, in fact many were against it and some still are uncertain. Time has shown that when presented with high quality, innovative curriculum to meet the challenges of the future of work enthusiasm among faculty is contagious.”

Nancy P. Crimmin, Ed.D., President, Becker College