Increasingly, faculty leaders are responding seriously to the call for more “culturally relevant pedagogy,” referring to more inclusive classrooms and pedagogical styles. This article draws on findings from a recent inquiry into how institutions are thinking about equity within pedagogy.

In late 2019 (prior to the COVID-19 pandemic), I conducted 28 phone interviews with both administrators and academics in higher education, from distinct universities. I spoke with leaders of Centers for Teaching and Learning, leaders in Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, and faculty in leadership positions. My research also included a review of timely literature on this topic. In this article, I share a quick snapshot of how institutions are responding to the call for culturally relevant pedagogy.

by Ashvina Patel, Ph.D., Research Analyst, Academic Impressions

Want more articles and reports like this one delivered to your inbox? Sign up for our free Daily Pulse on higher education.

The Words We Use

What do we call the effort?

“Decolonizing curriculum,” “decolonizing the classroom,” “culturally relevant curriculum,” “culturally responsive materials,” “inclusive pedagogy,” “inclusive teaching content,” “diversity in curriculum,” “hidden curriculum,” and “uncovering implicit bias” are just some of the words higher education institutions are using to describe a change that is both historic and new. In its most informed iteration, this effort essentially approaches classroom instruction (syllabi, reading, assignments, lectures, mentoring) with a mindset that recognizes how systems of oppression and structures of inequality have framed the history of knowledge production, creating a canon of androcentric, Eurocentric, heterocentric work that is reified at institutions of higher education. My own research was focused on:

- What types of efforts are underway within higher education to revise pedagogy

- Where such efforts can be found within a campus

- The connection between the words we use to describe these efforts and the institution’s history and culture.

When I provided a verbal list to interviewees about terms their colleagues are using to define this process—and it is a continual process— there were many expressions of displeasure. For example, some have found the word diversity to be a meaningless usage that serves to make higher education administrators feel better about themselves for attempting equity, but with little substance. (For example, see “Diversity Fatigue is Real.”) Another interviewee preferred the term inclusive teaching. “I would like for us to move away from a deficit model, where some students lack something, to one where every student benefits from teaching practices that are structured and promote engagement. There is no deficit, no privilege, just inclusivity” said Milagros Rivera, Director of Faculty Diversity, Inclusion and Well-being at George Mason University

Whatever we call this shift, there is a renewed movement based, in part, on the nation’s political climate. The political climate since 9-11 has been asking us to reflect, define, and challenge what it means to be American. This sentiment is mirrored to some extent on college campuses that are calling for specific attention to be paid to equity in the content being taught to students. Where does knowledge production lie? Who produces our understanding of the world? Need it begin and end with an androcentric, Eurocentric, heterocentric foci?

Institutions of higher education have responded well to the call for inclusive classrooms that requires an openness to disability and difference; and a pedagogical style that is accessible to all types of learners. But what students are demanding, and Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion leaders are aiming towards, is something more targeted: a pedagogy that is inclusive of perspectives outside of what Audra Lorde calls the “mythical norm,” or that which is “white, thin, male, young, heterosexual, Christian, and financially secure.” In some cases, pedagogy grounded in the mythical norm is dangerously inaccurate, and in others it silences the perspectives of the underrepresented.

The Catalyst: Why Institutions are Responding Now

One public research university in the Northwest created a position to aid campus efforts in hiring more diverse faculty members. Many institutions are struggling to find meaningful ways to not only recruit diverse faculty but to also retain them. “We are highly diverse at the student level but not so much at the faculty level,” one university official told me.

Students are aware of this—and much of the current movement toward culturally inclusive pedagogy is inspired by students. At that research university in the Northwest, a couple of years ago a student group convened, went to the president, and petitioned for more diverse faculty and a course that addressed issues of diversity and inclusion. Consequently, a new diversity class requirement was added to their core as an initiative led by student demand.

In my interviews alone, other such incidents across U.S. campuses that provoked change include student disruption of important presidential meetings, student sit-ins, a push by students to decolonize curriculum, request to create faculty buy-in for less American-centric curriculum, sexual assault, sex-based bias in classrooms, unwillingness to mentor female students, and/or microaggressions masked as ethnic jokes in ethnically diverse fields such as software engineering. These are all ground-up events that demanded a response from institutional leaders. In light of the current progress of the BLM movement, we can expect to see more disruptions coming to campuses this fall.

Different Structural Approaches We’ve Seen

Centralized Efforts

Centralized efforts build diversity into their campus culture in a meaningful way. One such suburban campus on the Northeast coast places diversity as its core mission. With a dynamic President at its helm, they embed an ethos of equity throughout the campus. Innovative curriculum is operationalized through several initiatives—incorporating students from both undergraduate and graduate levels. Service learning is a core principle; faculty and students work innovatively on large community projects on campus or in the city at large. They have a program to ensure diversity, equity, and inclusion are central to the faculty hiring process. And lastly, they developed a mentorship program for women faculty in STEM. A member of senior leadership said that having culturally relevant pedagogy is not a challenge for them because of their campus culture.

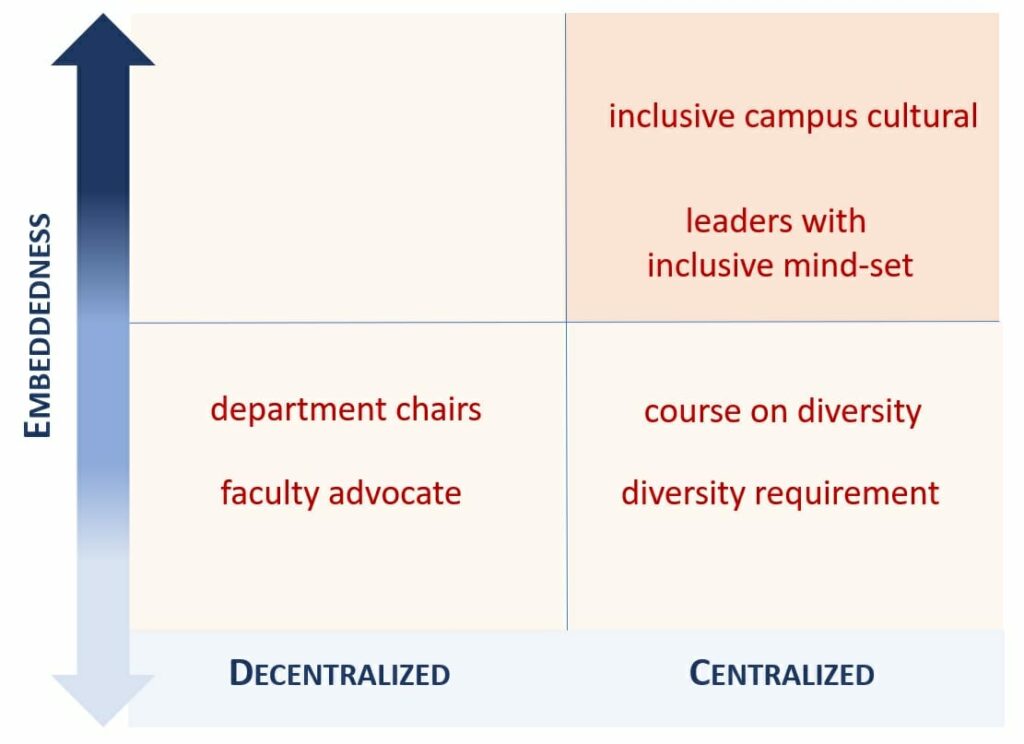

Campuses such as this are an example of a centrally-embedded model of equity. Other models that are centralized but not embedded include institutions that required a single diversity course or have a diversity requirement in which students are required to complete 2-3 courses that have been designated as having fulfill a diversity criterion. These two examples of equity-building are critiqued as treating diversity as a commodity for consumption as opposed to a mindset cultivated through everyday experiences at the university, most of all in the classroom.

Decentralized Efforts

In decentralized models you will find Centers for Teaching and Learning, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion officers, department chairs, and individual faculty advocates championing to create equity at the classroom level. Examples of these efforts include institutions like Utah State University where Dr. Idalis Villanueva, a National Science Foundation Early Career Development Program awardee researching hidden curriculum in engineering conducts training at their Center for Innovative Design and Instruction on hidden curriculum across disciplines.

“Hidden curriculum includes assumptions and unexamined rules, norms, beliefs, and attitudes that pervade a university environment that would indicate to several underrepresented groups how well they fit or not into the discipline.”

Dr. Idalis Villanueva, Utah State University

The work involved in getting to that upper-right quadrant of embeddedness evolves differently based on a multitude of factors. One factor is the geographic location of your institution.

Rural Institutions Face Greater Challenges

There is a divide in the development of culturally relevant pedagogy along a rural-urban axis. Urban institutions that come from a long-standing tradition of actively creating a culture of diversity, equity, and inclusion, do not struggle as much with pedagogical asymmetry. Their community, student population, and faculty are diverse, thereby creating a campus culture in which ‘norms’ are frequently challenged. One Vice President of Academic Affairs at a college in New York City said that diversity was not something they even think about in an urban space where the population they serve and the demographics there are in, are so diverse. “We just do it. It’s part of our fabric.” She stated that the challenge they are currently dealing with is to expand their professorship to those who speak bilingually to support student learning. Cultural sensitivity is built into their institutional grading rubric. At urban institutions equity within strategic plans and student support services can be targeted more precisely because they are not struggling with the elementary activities of defining equity and selling the benefits of diversity and inclusion to faculty.

In contrast, rural institutions often have a more homogeneous student and faculty population. At Utah State University, for example, a high degree of religious and racial uniformity exists, which can pose unique challenges. Neal Legler, Director of Center for Innovative Design and Instruction, observes that many people are open to addressing diversity issues but do not know how. “You will see microaggression from people who are well-meaning, but who are just dumb about race and diversity and inclusion. Opportunities for feedback and reflective learning around issues of diversity are more limited.” In rural spaces with little diversity it is also more difficult to attract faculty of color. Places like Utah State University that are actively working on being culturally responsive have developed external partnerships that bring workshops to campus.

Leaders at both rural and urban institutions agree that you must attract diverse faculty that can help lead culture change in order to have real pedagogical movement. It is noteworthy to add that not all faculty of color are automatically culturally competent about creating inclusive pedagogy. In fact, Centers for Teaching & Learning repeatedly stated that most of their internal diversity, equity, and inclusion themed workshops are attended by women and faculty of color. They call it “preaching to the choir;” however, that does not mean that the “choir” does not have their own set of implicit biases to work through. They attend in order to continue with the hard work of improving their pedagogical approaches. The work of decolonizing curriculum is embodied work in which one’s own historic relationship with knowledge production must be examined. It takes openness to dismantling one’s own worldview to expose bias.

Looking Ahead

The reasons universities should care to be involved in the process of inclusive pedagogy are both internally and externally driven. The global economy, and job markets are more diverse than ever before, requiring employment of those who can see through the lens of multiple perspectives. In order to meet this demand, institutions want to ensure they are graduating students whose knowledge is built upon a wider frame of reference than the West. They need be students who are culturally-informed, and well-experienced citizens who can speak to, react to, and thoughtfully consider building systems of equity across a broad range of industry.

Institutions of higher education are also in a unique moral position. They are called upon to build the future generation of global citizens, making their task a prescriptive one. What kind of a world do we want to build? And are we creating student experiences that foster this change? For example, universities with a diverse student body as well as those with homogenous student bodies, both must teach their students accurate histories that challenge structures of inequity, so that existing cycles of oppression can be dismantled.

Additionally, and perhaps most markedly, students are demanding change. In 2017, when Noelle Cockett from Utah State University was appointed president, her tenure was met with a priori accusations of sex-based discrimination, a refusal to mentor female student, and even assault against women at the university. Since, diversity, equity, and inclusion have become an institutional priority. There is student demand for equity, and a recognition by institutional leaders that it is incumbent on them to create a space where the institution does not perpetuate a system that allows young women to be treated differently than their male counterpart, for example.

No two institutions’ process will look the same because these changes are catalyzed by larger culture shifts that may be local, regional, or even global. The implication of such unique geneses is that there is no one-size-fits-all solution for institutions. It is only important that they begin the work, collaborate in that process, and continually strive towards inclusive and representative pedagogy; understanding that it is not a finite transaction.

The words we use in this effort of pedagogical reform are indicators of institutional history or current challenges. While certain language may not work in one region, it may for another. It would behoove institutions to pay extra attention to the language they use because it gives rise to identities and recognition of realities. For some, words matter a great deal. For others, the actions and the intent speak far louder. What is clear from my research findings is that in higher education there are students, faculty members, institutional centers, diversity officers, provosts, and many more who are the campus champions for this type of work. It takes work at all levels to summon the courage—and it is a courageous act—to press forward with creating culturally relevant pedagogy.

___________________________________

Image Credit: Photo by Peyman Farmani on Unsplash.

Additional Resources

There are many scholars producing highly relevant, thoughtful work in the area of culturally relevant pedagogy. These are just three examples who have informed my thought process here:

- Harrison, Faye V. Decolonizing anthropology: Moving further toward an anthropology for liberation. American Anthropological Association, 2011.

- Lorde, A. Sister outsider: Essays and speeches. Crossing Press, 2012.

- Love, Bettina L. We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press, 2019.

You can also dig more deeply into this topic in the time of COVID-19 by attending our virtual training Inclusive Pedagogy in Higher Education: A Mindset and Continual Practice. We know that in the wake of COVID-19, the rapid transition of moving courses online has left many students feeling isolated and insecure, and it has put the most vulnerable students at even greater risk. By using components of inclusive pedagogy in online courses, instructors have the unique opportunity to build community in a new way and create spaces for all students to come together and learn on equal footing.

Inclusive teaching is more than simply completing a checklist of best practices. This approach requires instructors to pair critical self-reflection with actions in the classroom. Join us for this highly interactive virtual training and dialogue to learn how to transform your teaching practices to better engage, support, and prepare your students without sacrificing rigor. In this virtual training, Dr. China Jenkins from Texas Southern University will guide our discussion and share strategies for cultivating a pedagogy of inclusion.