Also in this series:

Is it Time to Launch that New Academic Program? The Art and Science of Answering that Question

Feasibility Checklist: The Science of Bringing New Academic Programs to Life

Financial Modeling for New Academic Programs

Sustaining New Academic Programs: 5 Key Factors

In my previous articles in this series, I outlined a blueprint for new academic program development and stressed the importance of a balanced approach. Understanding that it is impossible to capture all variables on the front end, the potential viability of a program is difficult to assess until that program is up and running. While having a discipline around new program development ensures that you will anticipate most of the important potential impact issues, maintaining a culture of flexibility and responsiveness once the program is launched is equally critical for the program’s success. As the great American novelist Thomas Berger once wrote, “The art and science of asking questions is the source of all knowledge.” Indeed, cultivating a spirit of ‘question asking’ and ‘wide-eyed vigilance’ as a program is embedded within your organizational culture and context, while not easy, is nevertheless a foundational pre-requisite for long-term viability.

Over the past decade, we have successfully implemented and sustained more than twenty new graduate programs at Bay Path University. Having learned a great deal through this process, I have found a handful of key factors that are important to keep in mind:

- Think long-term with up-front investments.

- Leverage untapped potential.

- Start small, invest conservatively on the front end, and build as you go.

- Maintain a spirit of adaptability.

- Develop “Kaizen” eyesight.

Let me provide more context for each of these considerations.

1. Think Long-Term with Up-Front Investments

In considering new program investments, ask yourself whether an investment might have a broader and/or longer-term purpose? For example, when we launched our first fully online graduate program in nonprofit management and philanthropy, we also at the same time established a Center for Online Teaching and Learning. Given that our longer term strategy involved expanding our online presence across several programmatic areas, an investment of this kind on the front end and with our very first online program made sense. Likewise, when we hire program directors, we often look for individuals who have teaching expertise across more than one area. As much as possible, investments in personnel, facilities and other should be defensible in terms of their potential adaptability within a broader context.

2. Leverage Untapped Potential

In my experience, every campus has untapped potential and capacity if one is willing to look for it. With new program development, such untapped potential can be a valuable resource that enables you to build and achieve results more quickly. At Bay Path, we leveraged our historic expertise in educating adult women through campus based programs by establishing the fully online American Womens College, an entity that provides essentially the same curriculum through a new, innovative delivery and support model. Likewise, we recently established an OT Bridge program with a curriculum that builds off of our long-standing graduate program in occupational therapy. Utilizing some existing curricula, the OT Bridge program meets a critical professional pathway gap for individuals who have an associate’s degree in occupational therapy or physical therapy and want the master’s degree—without the duplication in content that one typically finds between the associate and upper level content in this field.

3. Start Small, Invest Conservatively, and Build as You Go

Because our Board of Trustees expects that we will break even as soon as possible, we have developed a discipline around starting small and investing only in the most critical expenses necessary until the program is up and running and we can better assess the full potential. This means we typically start with one full-time dedicated program director or chair and a cadre of adjunct faculty. Unless the program has external accreditation requirements which specify minimum staffing levels our program proforma ties personnel additions in subsequent years directly to enrollment growth. Once the program is up and running, we closely monitor net contribution results and make decisions about staffing additions as part of the annual budget process. Once we see signs of financial viability, we ramp up our investment while continually reviewing results and adapting as we go.

4. Maintain a Spirit of Adaptability

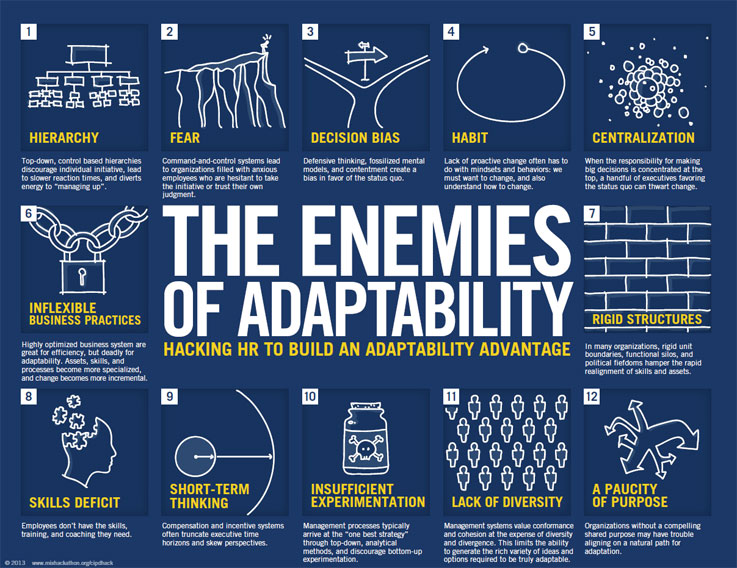

Maintaining a spirit of adaptability once a program is up and running sounds like an easy thing to do and yet, in most of our institutions, the pull toward the status quo is a difficult thing to resist. As the image below illustrates, the institutional culture and context is not typically conducive for the kind of flexible, responsive mindset that is needed in today’s academic marketplace:

Source: https://www.game-changer.net/2013/05/30/the-enemies-of-adaptability/#.WEGf3WxVVPa

As academic leaders, one must actively cultivate a spirit of adaptability and intervene when necessary to overcome these barriers.

For example:

- Adding ‘outside’ experts or advisors to internal committee processes is a wonderful way to nurture flexibility over time.

- Recognizing and rewarding adaptability whenever one sees it sends a powerful message about the value of such behavior.

- Mixing up work groups with individuals from diverse backgrounds and office areas as well as modeling a willingness to experiment and occasionally ‘fail’ are also powerful tools for building an adaptive culture.

Until a program is up and running, it is virtually impossible to fully know its marketplace potential. For that reason, one must be vigilant in monitoring program results and be quick to make changes in response to these results as warranted. In nearly every new program that we have launched, we have made changes in program design and content after the initial launch based on what we learned about market demand and student learning needs.

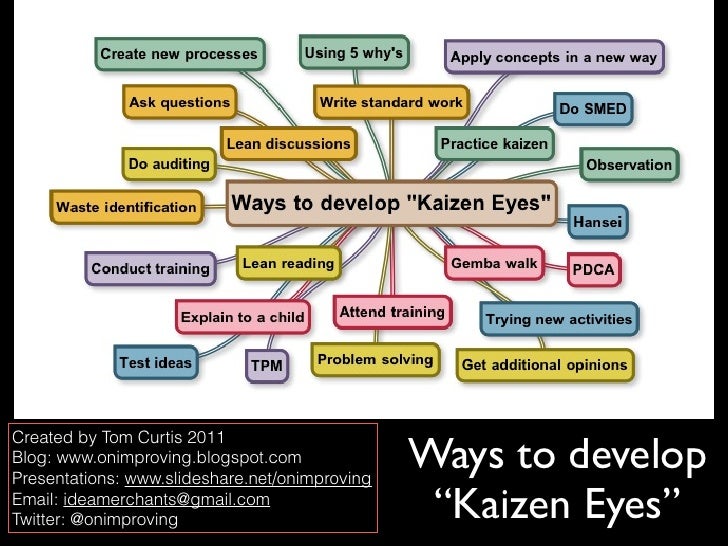

5. Develop Kaizen Eyesight

Kaizen eyesight is a Japanese philosophy originally adopted by Asian car makers and now a pivotal concept for the continuous improvement movement. Gradually making its way into higher education in recent years, Kaizen eyesight has to do with the practice of challenging preconceived notions about the way things should be. As demonstrated by the illustration below by Tom Curtis (2011), there are several ‘Kaizen-esque’ practices that one can employ to remain vigilant in one’s assessment of new program performance:

Source: https://www.slideshare.net/onimproving/ways-to-develop-kaizen-eyes

Especially during the first year of new program implementation, it can be helpful to have a series of questions that you ask to ensure you are accurately interpreting market response to your programs.

For example:

- To what extent does the demographic profile of your enrolling students match your preliminary assumptions about who would enroll?

- If there are significant differences, what do they mean?

- What factors have been most significant in your students’ enrollment decision?

- Why did they choose your institution generally and this program specifically?

- How strong is the funnel performance for this program (e.g. yield of applicants, accepted, and enrolled)?

- To what extent are your students’ learning expectations being met?

- How satisfied are they with their experience in this program and at your institution?

Having an external board of advisors made up of industry professionals who you utilize to observe, ask key questions and assess performance with you and your faculty can also be extremely helpful.

It Takes Both Art and Science

At the end of the day, I liken the process of academic entrepreneurship to that of a dance—a process that is highly fluid requiring one to be at once both disciplined and focused while remaining flexible and responsive to the context in which one is moving. This is the ‘art and science’ approach that has been pivotal to our success at Bay Path and is essential, I believe, for navigating the dynamic higher education landscape that most of us find ourselves in today.