Sydney Andringa

Executive Assistant to the Vice President of Institutional Advancement, College of Saint Benedict

Valerie Jones

Executive Director of Alumnae Relations, College of Saint Benedict

Heather Pieper-Olson

Associate Vice President of Institutional Advancement, College of Saint Benedict

Julie Reitmeier

Executive Director of Advancement Systems, College of Saint Benedict

In January of 2014, the Institutional Advancement Team at the College of Saint Benedict, a Catholic, Benedictine, liberal arts college for women in central Minnesota, faced a unique and complex set of circumstances. A brand new, first time, president was six months into her tenure; the vice president of institutional advancement (IA) had resigned and announced plans for a pair of interim vice presidents to lead the department; the college had just announced a $100 million comprehensive campaign; and the IA department had recently hired or was in the process of hiring four new staff members on a 24-person team. The president gave us, the senior leadership team in IA, a directive: create stability for the department and focus on retention of the current team. To create that stability and retain our workforce, we focused on creating a sense of belonging for all current and future staff members by creating an extended onboarding process. Not only would the four newest members of our team benefit, but the entire team could pool their collective knowledge and create a common shared understanding of our department from processes, to departmental traditions, to written and unwritten cultural mores. If we could accomplish this, we believed we would feel the stability and experience the retention we were asked to provide.

In this article we will share the steps we took to create and implement a high impact onboarding process, a description of the tools we created to use throughout the process, the steps we use to maintain and update the process, key learnings, the pitfalls and mistakes we made along the way, and the insights and outcomes of using the process.

Why Onboarding

Onboarding prepares new employees for success. It is the process of acclimating and welcoming new employees into the work environment and providing them with the tools, resources, and knowledge to become successful and productive. While orientation prepares someone for their first days of work, onboarding is a broader, long-term process that helps new employees acclimate smoothly, so that they become an engaged part of our team. This process starts before an employee begins and lasts through the first year of employment. From our point of view, orientation is an event; onboarding is a process.

Our college states that the greatest resource available to meet our mission is the human capital. As employees of the institution, we believed a process designed to care for these human resources could create and foster both stability and retention. There may be no more perilous place for an employee’s sense of belonging and purpose than the unarticulated culture of a department. We created a task force and charged them with developing a new onboarding process to support employee knowledge, satisfaction, and productivity. Now, five years later, the process has just undergone its third revision and has altered the culture of the entire department. More importantly, the process was built intentionally to foster a greater level of equity and inclusion enjoyed by all members of the team.

We built our process to complement and enhance the process our human resources department (HR) uses to hire and orient new employees. The departmental process picks up where the HR process ends. In addition, we have included the HR department onboarding tasks into our own plan so that the two work in concert with each other in support of the new employee.

The Process

With the task force in place, the development of our onboarding process used the next year to create and build. Almost all of the resources needed to complete our charge was staff time- about 1-2 hours a week per person. We follow these steps during the first year:

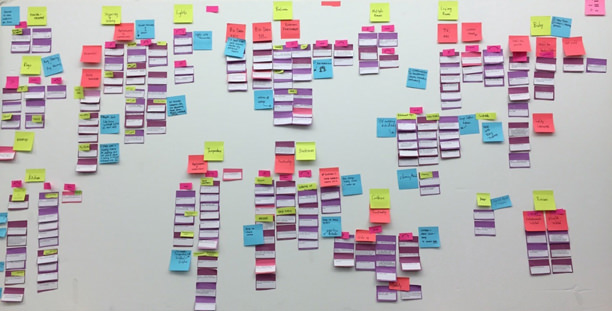

- Gather (about two months): The task force brought everything they has used, received, been told, or observed about their own onboarding process to a collective location. Each idea or element was written on a post-it note. No idea or element was too small and at the end of gathering our respective knowledge into one place we had thousands of post-it notes that covered three walls in our conference room.

- Brainstorm (one month): The next step the task force took was to use our own experiences to add new elements we wanted to see in an onboarding process, note the things we wished we had experienced but did not in previous onboarding experiences, and look at best practices or innovative ideas in other organizations. Each of these was written on a post-it note and added to our collection.

- Analyze (two months): We then used an affinity diagram (a process that organizes a large number of ideas into their natural relationships. to sort and organize the post-it notes into categories. The affinity diagram was the best method we knew of to both include and sort the incredible volume of ideas we had generated.

- Frame (one month): Based on our affinity diagram work, we quickly realized the best way to frame our work was around a timeframe, specifically: pre-start through a one-year anniversary of employment.

- Create (four months): From this framework we set a series of milestones on the timeframe and assigned each element of onboarding to a specific timeframe according to a developmental flow of knowledge and skill building that new employees face in a new work environment.

- Test, revise and refine (one month): We tested the process and the tools we created and made revisions based on our findings.

- Roll-Out (One staff meeting and a series of small group trainings over a one-month period): we conducted specific training for team members who would be filling the roles of onboarding mentors and onboarding supervisors. We then trained the entire team on how to use the process we created and shared tools that all employees could benefit from using.

- Maintain (Each update takes a team of 5 about 25 hours): We update and revise the process at least every two years or as needed due to unexpected changes or emerging needs. The task force reconvenes to walk through each of the tools and steps of the process making updates, revisions, and adding new elements.

The Tools

Creating a successful onboarding experience for every new employee and taking into consideration varying levels of supervisory experience, requires the right tools. There are many onboarding tools available, at differing price points and levels of complexity. In our case, the right tools would be free, simple, and straightforward. Our onboarding tools were created for the purpose of streamlining, guiding, and influencing the conversation from the time a new employee accepts an offer of employment, through their first year. To start, we identified a need for four written tools. These tools help make the onboarding process smooth for the employee, their supervisor, colleagues, and the institution.

Our four written tools are:

Supervisor checklist:

To be successful, our onboarding process heavily relies on the supervisor to be successful. The checklist is a detailed document, divided into sections – pre-arrival, first day, first two weeks, one month, three months, six months and one year. These sections include elements the supervisor is expected to handle, from sending an email hiring announcement to our staff, to explaining the role of our Board of Trustees. Some tasks reference additional delegates who the supervisor follows up with to complete or help with the task and others mention additional reference documents and or links to additional information. While this roadmap is designed to ensure the supervisor has all the elements needed to help get the employee off to the best start possible, the supervisors are encouraged to incorporate their own style and preferences into the process so that employees know what to expect and what they will be held accountable for accomplishing.

Supplemental checklist:

Our supplemental checklist uses the same format as the supervisor’s checklist. Every time the supervisor’s checklist references a delegated task, that task is listed on the supplemental checklist. Every person delegated by the supervisor shares the same supplemental checklist for a new employee. As a result, every person with an onboarding task knows exactly where and when that task falls into the onboarding cycle. Cross referencing is easy for both the supervisor and the delegate.

Office Protocol Guide:

The Office Protocol Guide is our attempt to reveal the unarticulated culture of our department. This document includes everything from where to find ATMs on campus to what you are supposed to do when there is a departmental “bell ringing.” This includes, dress codes, staff areas of expertise, terms of art, and how to ask for a day off. The goal of this document is to give everyone access to the unarticulated cultural norms and expectations within our department. When writing this document, the task force included any topic for which staff had differing knowledge or understanding. We included anything about which a task force member said “I never knew that” or anytime someone said “I assume…”

New Employee Folder:

Even in a digital age, people appreciate the reassurance and familiarity of critical information on paper. To that end, our onboarding process includes a new employee folder that includes critical information best presented visually.

In addition to the four primary written or printed tools used in our onboarding process, we developed four unwritten tools to support healthy onboarding for new employees as well.

IA Mentor Initiative:

We have assembled a pool of mentors within our department. Each new employee is assigned a mentor who is not on their departmental team or in the same reporting line. The mentor receives training and conversation guides to use with the new employee and monthly meetings are encouraged throughout the first year. The mentor is tasked with helping the new employee navigate culture, create safe space for questions and learning, and providing a source of support and encouragement during the ups and downs that come with every new position.

IA Tour Guides:

We also trained a few members of our team to be tour guides for a campus tour. More than a basic tour, this tool and step in the process is designed to create a sense of belonging and permission to be in and utilize the spaces on campus needed for meeting job expectations. It also serves as a functional way to begin introducing the new employee to key community members outside of the IA team. Finally, the tour guides are not the new employee’s mentor, supervisor, or team member so this step also means the new employee is developing important relationships with a wider number of people within the department.

Training:

The entire department is trained in how to use the onboarding process whether they are a supervisor or not. We conduct a training refresh every time we update the onboarding process and materials. This is a useful reminder for veteran staff as well. We continue to build competence, reaffirm values and expectations, and empower our staff through onboarding.

A team of onboarding experts:

The team that created the process continues to tend to its oversight and serves to support the entire department in using it. This team checks in with supervisors who are in an active onboarding cycle and tracks requests for changes, updates, or assistance. This team also works to share the process outside of our department as opportunity and influence arises.

Together, the written and unwritten tools create a smooth, highly detailed yet flexible path for a new employee and their supervisor. The process takes the guess work out of what should be covered and spreads the information out to make it both absorbable and just in time for when the new employee needs to know it.

How it Works in Real Life

Tools, whether written or unwritten, are only as good as the people using them. How this process works in real life is an important indicator of whether it actually fosters the kind of departmental community and culture that allows us all to do our very best work. After using the process for five years, we feel reassured that we have created something immensely useful.

The onboarding process and tools need to be updated as a team grows, or institutional changes occur. The tools are useful only if they reflect the reality of the space and priorities of the team they serve. The task force convenes at least every two years to walk through each of the tools and steps of the process making updates, revisions, and adding new elements. Changing circumstances and evolving needs might not fit neatly into a regularly scheduled bi-annual review process. When significant changes occur for a team, the onboarding process needs to be reviewed in a timely manner to make sure the process will still be helpful for new employees.

Teams and organizations change, and it is critical that processes reflect those changes. Consistent revision of our onboarding process allows for a smooth onboarding experience for every new employee when they join our team and the continuing evaluation of office culture.

Pitfalls and Mistakes

Creating a process this detailed and this broad was a complicated endeavor. We made mistakes along the way and encountered obstacles that we needed to overcome to complete our work. Here are some of them and what we learned from them:

- The level of detail was so profound that at times the task force members felt overwhelmed and tempted to quit. We overcame this obstacle by taking breaks, working in smaller groups on a specific or narrower task, and using the expertise of team members to determine who did what in the task force (for example asking those comfortable working in excel to work on the spreadsheets but asking the gift officer to consult with our HR office) so that everyone was working in their strength areas.

- Creating this process took an extraordinary amount of time. The task force spent a full year on the project and every revision takes a smaller team of 4-5 people another 5-10 hours. Giving the rest of the IA team updates and asking for their input along the way ensured everyone understood the value of spending time this way. If human capital is the most important resource the department has to do its work, no investment in that resource is wasted.

- To create the most effective onboarding we really had to know and understand our own office culture. From the hidden, unwritten rules about using the toaster to mismatched expectations about who should be in the office when, we discovered a ton of important information about ourselves and the way we work that lives below the surface. We had to resist the temptation to assume everything was known by everyone in the same way. We had to address the human dynamics of sharing space, with diverse teammates who have different purposes and responsibilities, and actively shape the shared cultural expectations we wanted to implement in our department.

- Finally, we had to resist the urge to leave the work of onboarding to our HR department, who excels at the technical and legal elements for all employees, but does not and could not understand the culture, expectations, and aspirations of each department on campus. From the beginning we wanted to build a process that place the care and support of our colleagues at the center so that they could learn, grow, and contribute as quickly as possible.

Key Learnings and Outcomes

As with any significant expenditure of resources, it is important that you evaluate the return on that investment. The intensive onboarding process, and the even more intensive process to create and update it, takes staff away from their primary job responsibilities. We have found the staff time on this process to be well worth it, both as a means for better preparing our workforce to be more productive more quickly, but also to foster the inclusive workplace culture to which we aspire. Here are a few of the most important lessons and outcomes of this process.

Illuminate the “Hidden Curriculum”:

A heavy emphasis on mentorship in our onboarding process applies lessons we learned institutionally in our quest to become a mentor-centered community. In 2016, Dr. Buffy Smith, currently the Interim Dean of the Dougherty Family College at the University of St. Thomas, spoke at a campus-wide Inclusion Visioning Day about mentoring to illuminate the “hidden curriculum” for our underrepresented students. In her book, Mentoring At-Risk Students through the Hidden Curriculum of Higher Education (2013), Dr. Smith explains that the “hidden curriculum” in higher education consists of “the unwritten norms, values, and expectations that govern the interactions among students, faculty, professional staff, and administrators.” (Apple, 1982, as cited in Smith, 2013) This curriculum is revealed to students with “institutional cultural capital and social capital.” Students who thrive in college master both the hidden and formula curricula. We began to explore what the “hidden curriculum” of our office culture. What information and knowledge is required to “decode, interpret, understand and navigate” (Bourdieu, 1986, as cited in Smith, 2013) the office of institutional advancement at the College of Saint Benedict? Which social relationships and networks are required of a staff member to acquire the information, resources, knowledge and skills to be successful (Coleman, 1988, as cited in Smith, 2013)?

The written and unwritten tools were developed always with this in mind. We assumed the supervisor could and would tell you the expectations of the role based on the job description, but we want to make sure unspoken expectations were verbalized. For example, attending campus events, like community forums or socials, are important to our team culturally. We feel, as fundraisers, they are great opportunities to make connections with our colleagues outside of the department that allow us to better tell the story of campus life. We also feel our office staff should attend these events because we believe every staff member is an ambassador of the institution in the community. We want our gift processor to be able to answer their neighbor’s question about why college costs so much. We also want them to hear directly from leadership about the strategic direction of the college. It is not at every organization that you have an opportunity to hear directly from leadership on a regular basis. So we are explicit about our desire, but also have the conversation about whether or not participation in these events or others are mandatory. Though we might like everyone to attend a social activity, we also honor that not everyone is comfortable in that setting. We are more accountable to articulating when things are truly mandatory, and why we think they are essential for job performance. And when they are optional, we are more accountable to not unknowingly penalizing staff who opt out. The process of uncovering the “hidden curriculum” requires a willingness to confront our biases and be honest about what is actually required of our staff to perform their job functions.

Foster Innovation and Change:

“We have always done it this way.” The familiar and mutually frustrating answer to the new staff member’s question, “Why do we do it this way?” As the supervisor, you are likely not proud of the answer, but let’s be honest, the middle of orientation is not the time to analyze the efficacy of said process or procedure. You have likely been short-staffed and there is so much to pass on to your new staff member. As the new person, you lack the context to evaluate whether this is the best way to do something, you are trying to listen and learn about your new place of work and culture, and challenging a longstanding tradition is not exactly the first impression you want to make.

For those processes or procedures that are merely inefficient or ineffective, we rarely get back to them after the new staff member is onboarded. Leaving them unchanged has consequences for the productivity of our office. Empowering the onboarding process team with identifying those pain points, and recommending changes, guarantees that the changes will be made, and made with various stakeholders’ input, communicated broadly, and universally adhered to. Sometimes the only obstacle to organizational change is bandwidth to make change.

Most of the needed changes we have identified and addressed through the onboarding process could be categorized as benign. But what happens when the reason you do things the way you do things is a product of more than just inertia? What happens if it is a product of a dominant culture, and not having a good explanation for “why” leaves members of your staff permanently on the outside?

At the College of Saint Benedict we use the phrase “transformative inclusion” to describe our campus commitment to inclusion. Inclusion alone suggests that there are those on the outside that we are inviting into our community, or in the case of onboarding to our staff. By contrast, transformative inclusion allows all members of the community, be they newcomers or long-term staffers, to have equal authority and access to shape our team culture, to be known and understood and for us all to be transformed by being in relationship with one another. Transformative inclusion calls us to be willing to understand the needs of all of our employees and create an environment where they can bring their full and authentic selves to work. In creating the onboarding process, we had to really evaluate the “whys” of many of our traditions, process, and even our culture. Being honest with ourselves about our dress code, our meeting culture, our celebrations, or our expectations (spoken or unspoken), demanded of us evaluation of whether or not we were truly meeting the needs of our coworkers. We were then able to change some of those practices so as not to center the dominant culture. Here are two examples:

- This became incredibly poignant during the COVID inspired shift to working from home. 96% of our team members identify as women and what they were managing in work and home life during all the stages of COVID shutdowns was incredible. Adapting our work culture- which was a traditional 8 to 4:30, no familial responsibilities format- to create flexibility, specifically in response to women’s workloads yielded incredible appreciation and loyalty from our team.

- Another small example of adapting our traditions came in the way we celebrated a “holiday” party. We moved away from a celebration before the holidays to after as a former coworker noted that it was a greater gift to our staff to not add one more thing to their to-do list, as they had a higher likelihood of bearing the bulk of the responsibility for making the holidays happen at home. Changing from a holiday party to a secular new year’s party during work hours, where we cater in and actually let our staff relax, is a more inclusive way to celebrate and team build.

Document the Stuff that Really Matters:

So much of this process is about improved communication. Though the process is thorough, the actual volume of information is not overwhelming. We persist in editing it down to what is really important. Like most mission-driven institutions, we are explicit about sharing our history and values with new staff members and made sure that was included in the resources. One thing we realized was missing from our onboarding process was a stated commitment to diversity, equity, inclusion and justice (DEIJ) that reflected the way we engage in our work. Our division wide DEIJ plan includes our shared definitions of DEIJ, anti-racism and anti-sexism commitments, as well as actions we are undertaking throughout the division to achieve our stated goals of becoming anti-racist and anti-sexist. One tactical item in that plan is having every member of the staff take the Intercultural Development Inventory (IDI). Along with sharing that plan with the new staff members, we have made taking the IDI a part of the onboarding process. They have the choice as to whether to meet with an IDI coach to go over those results, but we have the information on our team’s shared intercultural orientation in mind as we do DEIJ work, so we want to make sure everyone has a shared vocabulary and understanding. Improved Team Dynamics:

When workplace morale is low, we hear the inevitable call for greater transparency, clearer communication, and fewer silos. Onboarding will not eliminate the need for mechanisms for transmitting information, seeking feedback, and accountable leadership on your team, but it will highlight for staff where they can find the information that is readily available when they need it. Giving the hiring manager the space to focus on the transfer of position specific information by taking care of everything else, improves the relationship between the new hire and their manager. It eliminates gaps in information sharing, and also holds managers accountable to walking through the onboarding process.

Information learned during onboarding is not always retained but having the office protocol guide as a reference for employees – new and old – gives them access to it when they need it. It is especially important because it identifies who on the team they can go to for specific questions. The employee bios are specifically developed for that purpose. We have each employee answer three questions: “I have expertise in…,” “I can help you with…,” and “One thing everyone should know about my role in IA is…” We also firmly believe essential expertise exists at all levels of our department. The onboarding process honors staff members for their knowledge and experience.

Additional Wins

We continue to find added benefits from utilizing this process. Here are just a few:

- Being a member of this cross functional team responsible for onboarding has been great professional development opportunity for staff throughout the team.

- Sharing this process with colleagues across campus has built deeper connections and understanding as they apply it to their team’s culture.

- These principles were applicable to other processes like offboarding, student employee training, and volunteer management. The onboarding process is a model for us whenever we know that human capital needs to be carefully tended, where there is a lot of information to transfer, and we will need to repeat the process, especially at random intervals.

- Demonstrating to our newest team members that we really care. The first few days in a new place can be scary. Even when you are excited about the new opportunity. Taking the time to make sure that they know where to put their coat, find a glass of water, who they are going to eat lunch with matters. One of the values of our Benedictine institution is hospitality, we had better live that out when it really matters the most.

Conclusion

We began this process with a directive from the college president: create stability for our department during a time of incredible transition and focus on retaining current staff members. With a year of intense collaborative effort, we created an onboarding process that supports the holistic development of each new team member and fosters a sense of belonging. In turn, that sense of belonging shortens the time new colleagues need to begin contributing, thereby increasing productivity, while simultaneously strengthening camaraderie and satisfaction. Because the process is designed to provide a deep and comprehensive understanding of departmental culture and processes every current staff member has a role to play in onboarding new colleagues and has become deeply knowledgeable about the interconnectedness of our departmental functions. Finally then, this sense of interconnectedness has fostered a greater level of equity and inclusion as we recognize and feel the essential strengths and talents of each team member and are transformed by each other’s work.

The benefits of the IA Onboarding process have more than paid for the original and ongoing investment of building the process. Our high functioning team has surpassed unimaginable goals, illuminated our department’s culture for the benefit of every employee, and gives each member a sense of belonging to a mission focused team.

Work Cited

Smith, Buffy. Mentoring at-risk students through the hidden curriculum of higher education. Lexington Books, 2013.

Sydney Andringa is the executive assistant for institutional advancement and has expertise in creating efficiencies, project management, and customer service. Sydney has been on staff at the College of Saint Benedict for 5 years.

Sydney Andringa is the executive assistant for institutional advancement and has expertise in creating efficiencies, project management, and customer service. Sydney has been on staff at the College of Saint Benedict for 5 years.

Valerie Jones is the executive director of alumnae relations. Valerie has expertise in volunteer management, group and meeting facilitation, strategic planning, and event planning. Valerie has been on the IA staff at the College of Saint Benedict for 8 years.

Valerie Jones is the executive director of alumnae relations. Valerie has expertise in volunteer management, group and meeting facilitation, strategic planning, and event planning. Valerie has been on the IA staff at the College of Saint Benedict for 8 years.

Heather Pieper-Olson is the associate vice president of institutional advancement and shares her expertise in annual giving, higher education fundraising, higher education administration, and a broad understanding of most of IA work widely on campus and in the industry. Heather has been on the IA staff for 13 years.

Heather Pieper-Olson is the associate vice president of institutional advancement and shares her expertise in annual giving, higher education fundraising, higher education administration, and a broad understanding of most of IA work widely on campus and in the industry. Heather has been on the IA staff for 13 years.

Julie Reitmeier is the executive director of advancement systems and uses her expertise in annual giving, budget preparation, budget management, data analysis and process management to support the entire IA team. Julie has been on staff at the College of Saint Benedict for 20 years.

Julie Reitmeier is the executive director of advancement systems and uses her expertise in annual giving, budget preparation, budget management, data analysis and process management to support the entire IA team. Julie has been on staff at the College of Saint Benedict for 20 years.