In my last post on student recruitment, I mentioned that recruitment and admissions—although often thought of as the same thing—are actually very different functions at some universities. But because there are about 1,600 four-year public and private, not-for-profit colleges and universities that are at least nominally selective, the line and distinction between the two varies based on institutional type, market position, and mission.

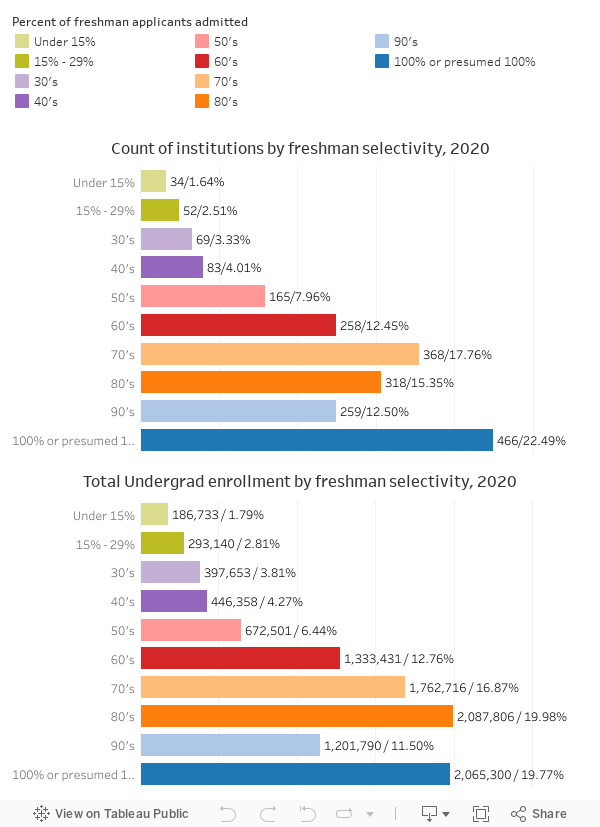

For context and clarity: IPEDS collects admissions data on all institutions that say they are not “Open Admission.” Looking at the 2,075 four-year public and not-for-profit institutions that admit freshmen and report admission data serves as the basis for discussion today; among them, we see that 466 are in practice or philosophy admitting 100% of applicants. Beyond that, however, there are millions of students enrolling at for-profit institutions and community colleges for whom admissions data is not available, and won’t be discussed here.

There is one thing admissions and enrollment professionals all agree on: If a student does not apply, they will never enroll. Thus, in a nutshell, recruitment attempts to generate as much interest, and usually as many applications, as is possible. Even if a university gets 20 applications for every seat it has in the freshman class, the American fascination with selectivity and the prestige and attention that accompany it generally means that “more is better.” For some universities, this desire for more applications is more a luxury than a necessity, often seen as nothing more than “keeping up with the Joneses.” At others, it’s a matter of ensuring that the institution is meeting its mission to serve a certain population. And at some other colleges and universities, it’s a matter of economic survival. It might be safe to say that admissions decisions often sit at the nexus of purpose, service, and finances.

I like to talk about admissions models—that is, the way that admissions offices serve their purpose as it’s articulated at each university. At the very highest level, I think of admissions offices as falling into one of three broad categories: 1) Those that deny large numbers of students they would like to admit if they had capacity that they could or would be willing to expand; 2) those who admit every qualified applicant and expand when demand grows to accommodate the growth; and 3) those who admit some students they are not sure about because their financial viability depends on it. Of course, these designations are not discreet; one needs only to hear of a few children of billionaires who gain admission to the most selective institutions despite their relatively weak academic accomplishments to understand that university finance plays a role in almost every office at some time.

While it’s impossible to say with certainty how many institutions fall into each category, I think it is safe to say that the second group is the largest; the first group is next, and the third group (those who admit students they’d prefer to deny) are the smallest.

Resource: For a thorough examination of admissions models, you might want to read Greg Perfetto’s 1999 work, “Toward a Taxonomy of the Admissions Decision-making Process: A Public Document Based on the First and Second College Board Conferences on Admissions Models.”

For some high-level context, here are summaries of the 2,075 colleges, broken out into selectivity bands. This is based on Fall 2020, self-reported IPEDS data.

As you can see, even calling the admissions office at all of these colleges by the same name belies the task they perform. The first group, those institutions with the well-known brand names of higher education, have admission rates in or near the single digits and the task is in large part deciding whom not to admit.

In 2020, just 34 institutions claimed admission rates of under 15%, and despite the disproportionate amount of attention these universities receive in the media, they enroll under 200,000 undergraduates among them (about 1.8% of the total in our group, and a far smaller percentage of the 16,000,000 total undergraduates in the U.S.). Admissions models at these universities are often compared to country clubs, or even to the newest and most popular night spots in Manhattan or Los Angeles: Admission is reserved for a select few, and it’s not always perfectly clear why these people gain admission.

Outstanding academic credentials are generally the starting point, but beyond that, softer factors such as leadership, athletic talent, legacy status, and wealthy or highly visible parents come into play. In the past few decades, admissions offices at these institutions have eschewed the “well-rounded student” in favor of a “well-rounded class,” filled with types high school counselors now call “pointy”—that is, students who are highly accomplished in one area. Even then, the admissions decision may be based in large part on econometric models that predict the students most likely to enroll, as a higher yield rate can increase the selectivity of the institution even more.

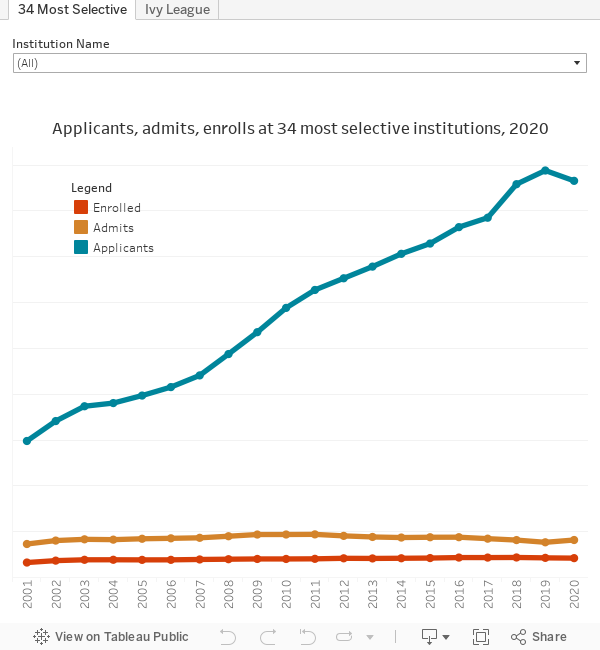

Competition at these institutions is hot, and the Groucho Marx adage about not wanting to join a club that would have him as a member seems to ring true; the more selective these colleges get, the more applications they seem to get. These institutions have seen massive growth application numbers over the last decade, but the total number of admitted students and enrolling students has stayed relatively flat over time. So, in some sense, recruitment and admissions work together to build and expand upon the reputation of the institution.

The vast majority of universities, despite our media fascination with what Akil Bello has dubbed “The Highly Rejective Colleges,” admit the majority of students who apply for freshman admission. Of course, this means that the largest percentage of people in higher education work at institutions like this. Want proof? IPEDS data for Fall 2020 shows that about 88% of institutions admit at least half of the students who apply as freshmen; collectively, they enroll about 88% of all undergraduates.

At those institutions, the admission process is simply a way station in the enrollment process that requires some sort of stamp of approval by an admissions officer, which is applied with more or less discretion depending on the college’s place on the selectivity scale. Of the many admissions models that might be in place at these colleges and universities, I dub this one “The Disney World Ride Model.” It’s also referred to as the “Gatekeeper” approach, where an admissions officer stands guard to make sure only qualified students are admitted.

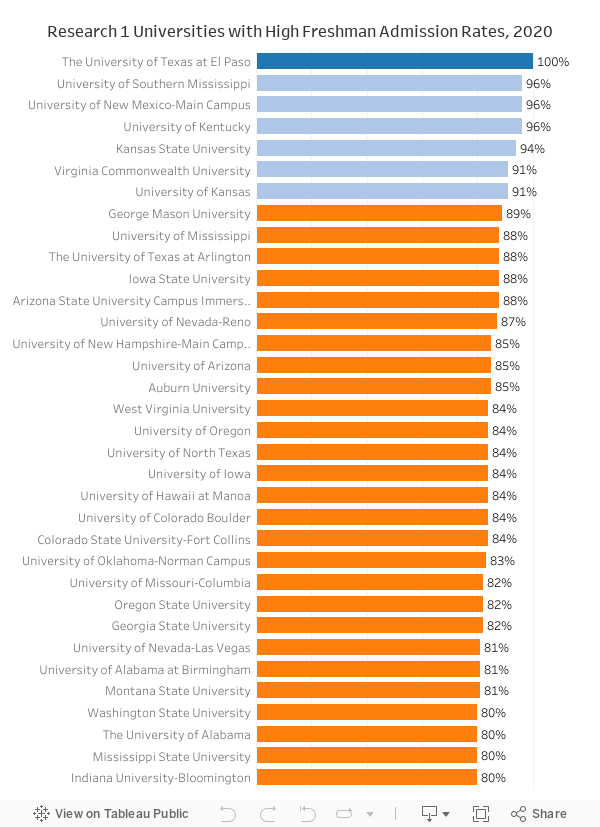

Neither one of these labels should be considered offensive in any way. In fact, in 2020, in a coincidence that rings somewhat poetic, there were also 34 universities classified as “Very High Research Doctoral Institutions” with freshman admission rates of 80% or higher. One of them, Arizona State University, says in its charter, “We are measured not by whom we exclude, but by whom we include and how they succeed.”

The “You must be this tall to ride” approach is one that is a breath of fresh air for students and parents who often hear the hype about college admission and are convinced that there are no reputable universities that are accessible.

For all their differences, admissions offices across the spectrum of institutions do, in fact, have many things in common. Whether that office is attempting to choose one out of 15 to admit, or trying to generate more so that it can admit almost everyone, admissions officers generally have a keen sense of what it takes to succeed at their institutions. It is this focus on the student that often means that admissions officers at all institutions—not just the highly selective ones—will deny admission to students they might have a soft spot for.

It’s not uncommon for admissions offices to “shape the class,” although selectivity generates the luxury of increased control over that shaping exercise. And finally, when admissions officers get together to share notes, two other themes emerge: First is that few people on campus seem to recognize the effort that goes into recruiting, admitting, and enrolling students to the university. You can trust someone who’s done this work for almost 40 years—it’s a lot harder than it looks.

The second thing we all seem to agree on is that the expectations always increase, sometimes even before the students are moved in for the fall. Regardless of the class that enrolls, and regardless of how it compares to previous classes, there is always someone who wants more students, more revenue, more diversity, more high-achieving students, or more first-generation or low-income students. And who doesn’t think you need to give anything up to get them.

Much of higher education has capacity today, as I wrote about here, and the situation has only gotten worse since this data in the Fall of 2019. Recruitment and admissions staff see firsthand the challenges each university faces, and they are often among the first that people turn to when attempting to address them.

So, high-five your admissions staff members the next time you see them?

Recruiting and admitting students isn’t easy, and neither is it sufficient. In my next post, I’ll be writing about financial aid and how it, too, is probably more complex than you might think if you only look at it from the outside.